Be careful with redistribution

We all want to combat poverty, but we should be careful with redistribution. Looking for the best distribution with the help of John Rawls, Corrado Gini, and the tv show Survivor.

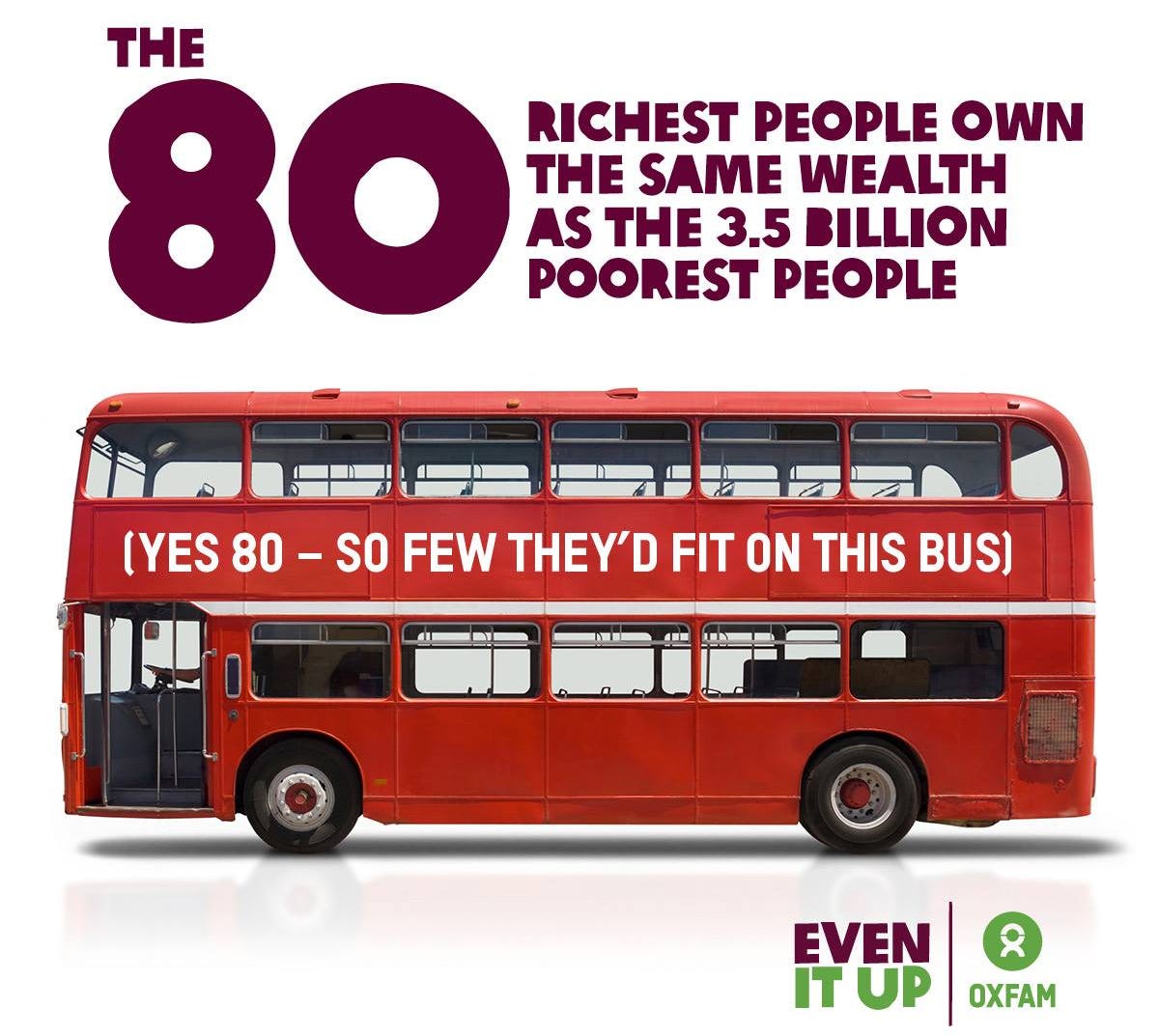

Previously, I wrote that differences in wealth arise naturally. One person has more talent, diligence or luck than another, or a rich dad. When differences in prosperity arise, there will always be a call for redistribution. The strongest shoulders carry the heaviest burdens. You can't leave those poor devils out in the cold. Everyone has the right to a dignified existence. You're going to hear those kinds of slogans. Or the proletariat seizes power. Because there are many of them.

A strange term by the way, redistribution. As if there is a bumbling Great Distributor whose work has to be done over again. But let’s stay focused. I want to find out whether redistribution is good, and how to do that, redistribute.

What is good? In other words: what criteria do we apply if we want to assess what is good for society? For now I'll just use:

Harmony: absence of conflict, presence of trust.

Economic growth.

We can also approach the question of redistribution ethically. For example, with the question that I often ask: do we owe each other redistribution? One might also call that justice. We'll get to that later. Let’s start with harmony.

People in egalitarian countries trust each other more

When there are large differences between rich and poor, people trust each other less. That has been studied a lot. Participants were asked questions such as: “There are only a few people I trust completely,” and: “If you're not careful, people will take advantage of you.” As the differences between rich and poor increase, more people will confirm such statements. As wealth differences increase, social trust decreases. Social hierarchies emerge, increasing anxiety and group conflict. Social trust is crumbling; people are getting tougher and more anxious, they isolate themselves, live behind high fences, talk less to each other, and only do business with each other if they know each other inside and out, or only with the intervention of lawyers and big contracts.

Do wealth differences also lead to crime? That's the question. There is no dispute that poverty and crime often go hand in hand. But with larger wealth differences, this correlation does not increase. In other words: is inequality really the problem? It seems to be more about poverty than about the difference between rich and poor. In fact, even the causal link between poverty and crime is brought up for discussion by some. There may be factors that can cause both poverty and crime. Culture, environmental factors and intelligence are obvious candidates.

Wealth differences do not necessarily lead to group conflicts. These usually have other causes, such as tensions between ethnic or religious groups. But if there are differences in wealth between such groups, there is a greater risk of violence, as in Sri Lanka, for example. In an article about group conflicts I will delve deeper into the conflict between Buddhists and Hindus in Sri Lanka, where the Tamil Hindus were (are?) structurally disadvantaged.

In short: things don't get any better when there are large differences in prosperity. Tensions are increasing and confidence is decreasing. But it does not necessarily become more criminal or violent. This requires additional problems, in particular ethnic or religious minorities in a persistently disadvantaged position.

Does equality and redistribution ensure economic growth?

And then: is economic equality good for economic growth? This question has been researched endlessly, but the conclusions are not clear-cut. In short, one could say that a certain economic equality is generally not bad, but one has to be careful with redistribution. And if we redistribute, we must focus on combating poverty. And if we want more equality, then redistribution is often not the best choice. I'm going to explain that.

Maybe I'm being Captain Obvious, but why is economic growth actually important? Because we are less in each other's way when it comes to economic growth. Suppose you form a family with a fixed income that never increases. Your daughter wants horseback riding lessons. Your husband wants solar panels on the roof. Your car is about to collapse. These are competing wishes. If income isn't growing, you can't achieve one thing without sacrificing something else. No summer holidays this year? It might end up in a row. With a growing income, we can achieve new things without sacrificing anything else: there are fewer losers. From a social point of view, we can also do this with economic growth: there is less conflict, hopefully less poverty, and more room to invest in long-term goals.

Inequality

Let's start with the economic benefits of inequality. With more inequality, people want to work harder because that yields more. The poor want to work hard because they don't want to be poor. People who are not poor also want to work hard, because they want to become rich. People with high incomes also want to work hard, because their incomes and profits are hardly taxed.

But now the economic disadvantages of inequality.

With large income differences, the small financial upper layer usually pulls the strings. There is more corruption, and the elite has no interest in sharing wealth with others. As a result, less is invested in things that benefit everyone: affordable healthcare and accessible education for everyone, for example. The system of inequality therefore perpetuates itself; it is difficult for talent to escape the underclass.

The rest of the disadvantages of inequality actually have little to do with inequality itself. It is mainly about the disadvantages of poverty. Researchers and ideologues often confuse these.

Poverty

Poor people receive poor education, poor health care, have lower life expectancy and larger families. With poor education we do not use the talent that could have contributed greatly to the prosperity of our country. Those who are poor have an incentive in having many children: that is their provision for old age. But those who have many children have even less money to invest in their education. That's the poverty trap: poverty perpetuates itself. The poor are also less eligible for credit, which means that entrepreneurship does not get off the ground enough.

Redistribution

Redistribution can have an inhibitory effect. If you skim off too much profit, every entrepreneur will throw in the towel. If you have to give up a large part of your income, why would you take risks, work hard, or invest in a long and expensive education? The more profits we tax from entrepreneurs, and the higher the tax for high incomes, the less investment, and the less risk is taken.

But if a moderate tax regime is used to provide better education, health care and income support for the poor, everyone ultimately benefits.

The level of education rises. Broad accessibility to higher education has a clear effect. The children of the poor are given the opportunity to escape their parents' poverty. And with easily accessible access to higher education, we utilise the economic potential of our population. Moreover, the population becomes economically and politically wiser, more moderate, and less susceptible to populism.

Income support and good health care for the poor also lead to smaller families; the cycle of poverty is broken.

A reasonable tax rate does not harm a country's economic growth, provided it is used wisely. Even entrepreneurship is not really affected. If an entrepreneur cannot bear a moderate tax rate, then entrepreneurship may not have been such a good idea for her anyway.

All in all, redistribution from rich to poor in countries with poverty and large wealth differences appears to have a net positive effect.

The limits of redistribution

I wrote that a moderate tax rate does not have to be harmful. But there are limits to that. The beneficial effect of redistribution appears to be reversed as soon as taxes become too high, hampering entrepreneurship and innovation. As a rule of thumb, redistribution seems to be helpful to maximum roughly 13 Gini points*. If the maximum is exceeded, it hinders economic growth. For poorer countries with high inequality, those 13 Gini points may be sufficient to combat poverty, but not necessarily to raise inequality to European levels. But the question is whether that is necessary. Countries with a Gini coefficient above 40 (such as Chile, and Singapore at the time) appear to still be able to make major economic progress. In fact, if there is little poverty in a country, it does not matter for economic growth how high or how low inequality is.

Can we also combat poverty without redistribution?

We want to reduce poverty as much as possible, but we have to be careful with redistribution. This raises the question of whether we can also combat poverty without redistribution. Because then we reap the benefits without suffering from the disadvantages of redistribution. And indeed: that is possible! Redistribution with taxes and benefits is of course the easiest and quickest to change, but we have to be careful with that. But there are other possibilities.

The protection of property rights, an effective bureaucracy and a strong rule of law show beneficial effects. And high employment, of course, as well as low inflation.

In addition, we might think of charity. Judaism, Shia Islam and Protestantism are well known in that respect. Not surprisingly, charity increases when less is redistributed. The advantage is that the redistribution is then voluntary. But charity usually creates a relationship of dependency, whether it comes from the state, from a religious organisation, or from well-meaning wealthy citizens.

Furthermore, a (higher) minimum wage is a simple method to moderate economic inequality without income transfer. One factor I can't immediately explain is the relationship between industrialisation and income equality: the more people work in industry, the greater the income equality. Perhaps this is related to the presence of unions, which (if all goes well) fight for higher incomes for low-paid workers. The disadvantage of minimum wages and wage demands from trade unions is the risk that employment will decline.

Equality and redistribution do not necessarily ensure economic growth

In summary, the following can be said about the connection between inequality, redistribution, poverty and economic growth.

Many researchers have examined the economic effects of inequality. The conclusions were never unambiguous. But they overlooked the elephant in the room. If you look at the economic effects, it is much better to focus on combating poverty instead of combating inequality. Combating poverty has major social and economic benefits. If you can eliminate poverty, it does not matter for the economic future of a country how high or how low the wealth differences are.

When it comes to combating poverty, a Robin Hood is unavoidable: taking money from the rich to give to the poor. There is nothing wrong with that from an economic point of view: as long as you redistribute in moderation, it will only benefit the economy in the longer term. This effect will be even stronger if investments are made in affordable access to higher education and healthcare for everyone. But from an economic point of view it makes no sense to strive for the lowest possible inequality at all costs: if you redistribute too much, you run the risk of economic damage. Instead, it is better to invest in an effective bureaucracy and rule of law, in high employment and to keep inflation low. If employment is high, there might also be room to increase wages, under pressure from trade unions or through the introduction of a (higher) minimum wage.

Is redistribution morally better?

I repeat: large differences between rich and poor have disadvantages, but so does large-scale redistribution. Taxation to further reduce income differences does not have to be harmful, as long as you do not overdo it. The disadvantage of taxation is of course that it is a form of coercion. As I have often argued: try not paying taxes for a few years and see where you end up. Behind bars probably. If that isn't coercion ...

One needs a good reason to use coercion. If you can prove that redistribution is morally better, you may have an argument for forcing people to redistribute. But is redistribution morally better than letting things take their course?

To justify forced redistribution, the American philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) wrote an influential book: A theory of justice. Rawls has made significant inroads among political philosophers. His portrait still hangs above the door of many departments, so to speak. In what way was he so revolutionary? Let's take a step back in time to Karl Marx.

Marx advocated redistribution. Formal equality was not enough. What good is the right to vote if you have to beg for a piece of bread? The class society may be a thing of the past, but other differences between groups of people also began to stand out: between people who had access to production factors such as land, capital and technological knowledge, and people who only had their own labour as a production factor. Without access to other factors of production, they were condemned to make their labour available as proletarians to the capitalists who could use their knowledge, capital and land. The factors of production had to be redistributed, Marx thought. But Marx was not an unequivocal egalitarian. He was particularly interested in the class struggle and in placing the means of production in the hands of the state. He only spoke in general terms about the final distribution: redistribution had to proceed “according to need”.

Each according to his abilities, each according to his needs!

— Karl Marx, Kritik des Gothaer Programms (1875)

The social democrats, a major power factor in post-war Europe, were also not clear about egalitarianism. In practice, a welfare state was set up in collaboration with the Christian social movement under the motto 'spread of knowledge, power and income'. But a sound theoretical basis for egalitarianism was not established until the publication in 1971 of Rawls' A theory of justice. His influence on egalitarian thinking is still great.

A veil of ignorance

John Rawls believed that we should look at what people would choose if they did not yet know what position they would occupy in society. Will you be poor or rich? Healthy or unhealthy? They have no idea yet. So they choose a society that everyone regards as just and fair in advance. If someone complains about the redistribution afterwards, if they think it is too much or too little, Rawls would speak sternly to them. After all, they made their choice when they didn't yet know whether they would be rich or poor. Now that they know that, they shouldn't complain, because now their opinion is coloured by your position.

He called his thought experiment the veil of ignorance:

No one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does any one know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like. I shall even assume that the parties do not know their conceptions of the good or their special psychological propensities. The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance. This ensures that no one is advantaged or disadvantaged in the choice of principles by the outcome of natural chance or the contingency of social circumstances. Since all are similarly situated and no one is able to design principles to favor his particular condition, the principles of justice are the result of a fair agreement or bargain. For given the circumstances of the original position, the symmetry of everyone’s relations to each other, this initial situation is fair between individuals as moral persons, that is, as rational beings with their own ends and capable, I shall assume, of a sense of justice.

— John Rawls, A theory of justice (1971)

Rawls’ veil of ignorance is a brilliant idea because it encourages us to explore how conflicts can be resolved in an objective, fair manner. But I am less pleased with his elaboration. If we had to choose behind that veil of ignorance, there is logically only one multiple principle that people would choose by which society should be ordered, Rawls thought. Now let us look at that multiple principle.

Equal freedom and levelling

Before Rawls got around to redistribution, he emphasised that as a first principle, equal freedom applies. This principle ensures that everyone can enjoy the greatest possible equal share of basic freedoms. In concrete terms, this means that redistribution is only allowed if everyone's equal freedom is respected. Interestingly, Rawls did not include economic freedom.

Secondly, Rawls thought that citizens would opt in advance for a society of solidarity. A society in which the rich take care of the poor, and where everyone has equal opportunities. This solidarity-based society would be organised according to two principles: the difference principle and the principle of fair equality of opportunity.

According to the difference principle, the basic structure of society must be organised in such a way that the well-being of the least advantaged individuals is maximised. In other words, everything, not just income and wealth, should be distributed in such a way that everyone gets the same, unless the poorest would benefit more from an unequal distribution. Let me explain the latter.

Some people are better than others at adding value. Suppose you have two million lying around somewhere. Of course you want a return on that. There are two people raising their hands: both Warren Buffett and I would like to invest that money for you. You decide to split it fifty-fifty. You come back after a year. Ashamedly, I admit that I lost two hundred thousand on it. But Buffett, possibly the best investor in the world, has made a twenty percent return. Equal distribution was not a good idea in that case. If you had entrusted all the money to Buffett, you would have made 400,000, and now you have nothing. With your high return you could have helped a lot of poor people, more than if you had handed out the money right away. That is why Rawls sometimes considered unequal distribution justified. In a capitalist system - provided that almost all profits are skimmed off and redistributed - the poor are much better off than in a communist system. That’s what Rawls thought. According to Rawls, we should let entrepreneurs do their thing, but we should take away their profits so much that they are hardly willing to continue doing business.

According to the principle of fair equality of opportunity, arrangements in society should be made so that people from poor and rich backgrounds with the same motivation and talent do equally well on average in acquiring coveted jobs and positions. Every effort must be made to ensure that, for example, equally suitable women, the poor and minorities are proportionately represented in the better professions. If this can only be achieved by giving those groups a priority position in education, for example, then so be it. We will talk about equality of opportunity in the next episode. For now we will stick to redistribution.

Rawls tested

Rawls was pedantic in his book. He was sure that rational, well-informed citizens would make the same choice he did from behind their veil of ignorance. Let’s see about that, thought a group of political scientists in 1987, and they devised a way to empirically test Rawls' theory. Others followed later. It was sad for Rawls, but none of the subjects chose Rawls' redistribution from behind their veil of ignorance.

Do you know the TV show Survivor, in which a group of strangers are dropped into a remote wilderness? Imagine being approached by producers who have something like this in mind, but far more extreme. You and your fellow players end up in a completely unknown environment, completely isolated from the outside world, perhaps on another planet. What you know is that with talent, effort and a good dose of luck, you can ultimately live like a King in France. But you have no idea what your starting position will be, what rules will apply, you don't know what skills you need, let alone whether you are good at them. It is quite possible that you will end up in a group that is severely discriminated against. There may even be slavery. You could also be struck by a fatal disease, there is a chance that you will have to suffer a deadly illness, or that war will break out and you will perish. And: you can never go back.

The producers offer you the option to take insurance in advance. With this insurance, you can eliminate the biggest risks. The downside is that the yields then also become proportionately smaller.

You can choose from the following insurance packages:

A. There is no competition; all proceeds are shared. The advantage is that no one is worse off than the other, but the disadvantage is that the entire group becomes passive: no one has the appetite to take initiative. Added up for all participants, this option leads to the lowest return.B. There is competition, but the one who is best off has to pay to the losers so much that his initiative is only just paying off. The losers are slightly worse off than in package A. Added up for all participants, the result for all participants is slightly better than in package A, but not much.C. There is free competition, but the participants who win help the losers in such a way that the distance between winners and losers never becomes too great. The added yield is greater than in package B.D. There is free competition, but the winners ensure that all participants can at least survive and not die of hunger. The average yield is approximately the same as with package C.E. There is free competition, no insurance. Those who die of hunger can only hope for compassion. On average, the yield is not really higher than in packages C and D. But for those who are successful, this is the most attractive package.There are roughly three possible outcomes: you lose, you win, or your outcome is the average of the group result. You have no idea in advance what your outcome will be, but the chance of each outcome is one in three.

In the aforementioned experiment in 1987, such a choice was presented to 29 groups of students. Twenty-five groups chose package D. The rest, four groups, opted for package E. No one chose package B, Rawls' package. (The radically egalitarian package A was not part of the experiment.)

It is known that people are naturally risk-seeking in the face of potential losses and risk-averse in the face of potential gains. Interestingly, people are more risk-seeking in the face of potential losses than they are risk-averse in the face of an opportunity for gain. People who receive 50 quid and are allowed to bet that amount for a 50 percent chance of doubling and a 50 percent chance of nothing, usually choose not to gamble. They prefer to keep the 50 quid. But conversely, suppose you are stopped for a traffic violation. The fine is 50 quid, but the traffic policeman has a proposal. He can flip a coin. You don't have to pay anything when it’s heads. But if it is tails, the fine is increased to 100. In that situation, most people choose to take the gamble: they let the officer toss the coin. While the probability of gain or loss is the same, as is the amount, most people behave differently when faced with potential loss than when faced with possible gain.

This suggests that most people would choose package E. The chance of being in group red is the same as the chance of being in group green. But when faced with the risk of loss, people are more risk-seeking than when faced with opportunities for gain.

On the other hand, with package E you run a serious risk of starvation. Does that risk weigh up against just as good a chance of a life in the land of plenty? Apparently not for the students who did the experiment, but they knew that no one would actually starve to death. Would the outcomes be different if the knives were out? Recent research does not indicate this. People become slightly less risk-seeking when faced with major risks, but the difference is hardly worth mentioning.

The morality of redistribution

Rawls' theory is madness. He demands that we systematically give priority to those who are the worst off, even if, objectively speaking, they are not that bad off at all, and helping those unlucky persons entails enormous costs. Rawls would cancel the game if one player suffered a sprained ankle.

We want to help people who are in trouble. If we camp in the mountains with a group of friends, we go a lot further. Then fair sharing is the motto. But the modern world is not an excursion with friends. We can deal with inequality, as long as there is intervention in the event of dire suffering.

When we consider people who are significantly worse off than ourselves, we do very commonly find that we are morally disturbed by their circumstances. What directly touches us in cases of this kind, however, is not a quantitative discrepancy but a qualitative condition — not the fact that the economic resources of those who are worse off are smaller in magnitude than ours but the different fact that these people are so poor. Mere differences in the amounts of money people have are not in themselves distressing. We tend to be quite unmoved, after all, by inequalities between the well-to-do and the rich; our awareness that the former are substantially worse off than the latter does not disturb us morally at all.

— Harry Frankfurt, Equality as a moral ideal, Ethics (1987)

The fact that most students chose package D is another argument in favour of sufficientarianism. People want responsibility for their own behaviour, even if the consequences could be bad. But that responsibility is not unlimited: we stand up for people who get the short end of the stick. They may feel the consequences of their failure, but we don't let them perish. In the last episode in this series, I will further elaborate on sufficientarianism.

To conclude

It will come as no surprise: I am not in favour of exuberant forced redistribution, on either economic or ethical grounds. Excessive forced redistribution sucks the dynamics out of society and exceeds what we morally owe to each other. This does not alter the fact that redistribution can indeed be useful, also as a moral obligation. I discuss how I see that in the last episode in this series, about sufficientarianism.

But we're not quite done with egalitarianism yet. Because we have not yet talked about equal opportunities and affirmative action. Moreover, I have smoothly avoided another question: should we only redistribute money, or everything that can make a person happy? Access to an education, for example, or access to a job, or even all forms of welfare? Those two issues are related. We'll go into that next time.

Read more?

John Rawls, A theory of justice (1971)

Norman Frohlich c.s., Laboratory results on Rawls's distributive justice, British Journal of Political Science (1987)

Harry Frankfurt, Equality as a moral ideal, Ethics (1987)

Liqun Cao, Yan Zhang, Governance and regional variation of homicide rates: evidence from cross national data, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology (2015)

Wesley Peterson, Is economic inequality really a problem? A review of the arguments, MDPI Social Sciences (2017)

Karim Bahgat c.s., Inequality and armed conflict: evidence and data, Peace Research Institute Oslo (2017)

Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, Inequality and conflict — some good news, World Bank Blogs (2018)

Andrew Berg c.s., Redistribution, inequality, and growth: new evidence, Journal of Economic Growth (2018)

Brandon Parsons, Panel data analysis of determinants of Gini coefficient (diss., 2021)

Believe Mdingi, Sin-Yu Ho, Literature review on income inequality and economic growth, MethodsX (2021)

Akira Inoue c.s., Making the veil of ignorance work. Evidence from survey experiments, in: Tania Lombrozo et al. (ed.), Oxford studies in experimental philosophy (2021)

Joe Hasell, Income inequality before and after taxes: How much do countries redistribute income?, Our World In Data (2023)

Han Bleichrodt, Olivier L'Haridon, Prospect theory’s loss aversion is robust to stake size, Judgment and Decision Making (2023)

Robert Breunig, Omer Majeed, Inequality, poverty and economic growth, International Economics (2020)

Thanks to Gideon Magnus who saved me from serious slip-ups in this article.

This was the third episode in a series about equality, redistribution and toleration. Here you’ll find an overview of all articles in this series. The next episode will be about equal opportunities.