We need to talk about drugs

The war on drugs is arguably one of the greatest policy disasters in human history. But how to move beyond these catastrophic strategies without triggering a meltdown from mass substance abuse?

Drugs are dangerous. Not only for the user, but also for society. You will read here what can happen if too many people start using drugs. But the fight against drugs may be even worse than the disease. You can read here how the fight against drugs has turned into a fiasco. We have lessons from history, economic analysis and the theory of soft paternalism in hand. With this I propose a new drug policy that does not patronise people, but keeps the negative consequences of drug use under control.

A perilous partnership: opium and empire

Let’s rewind to a time when Britain’s own hand was more than a little heavy in the global narcotics game: the Opium Wars.

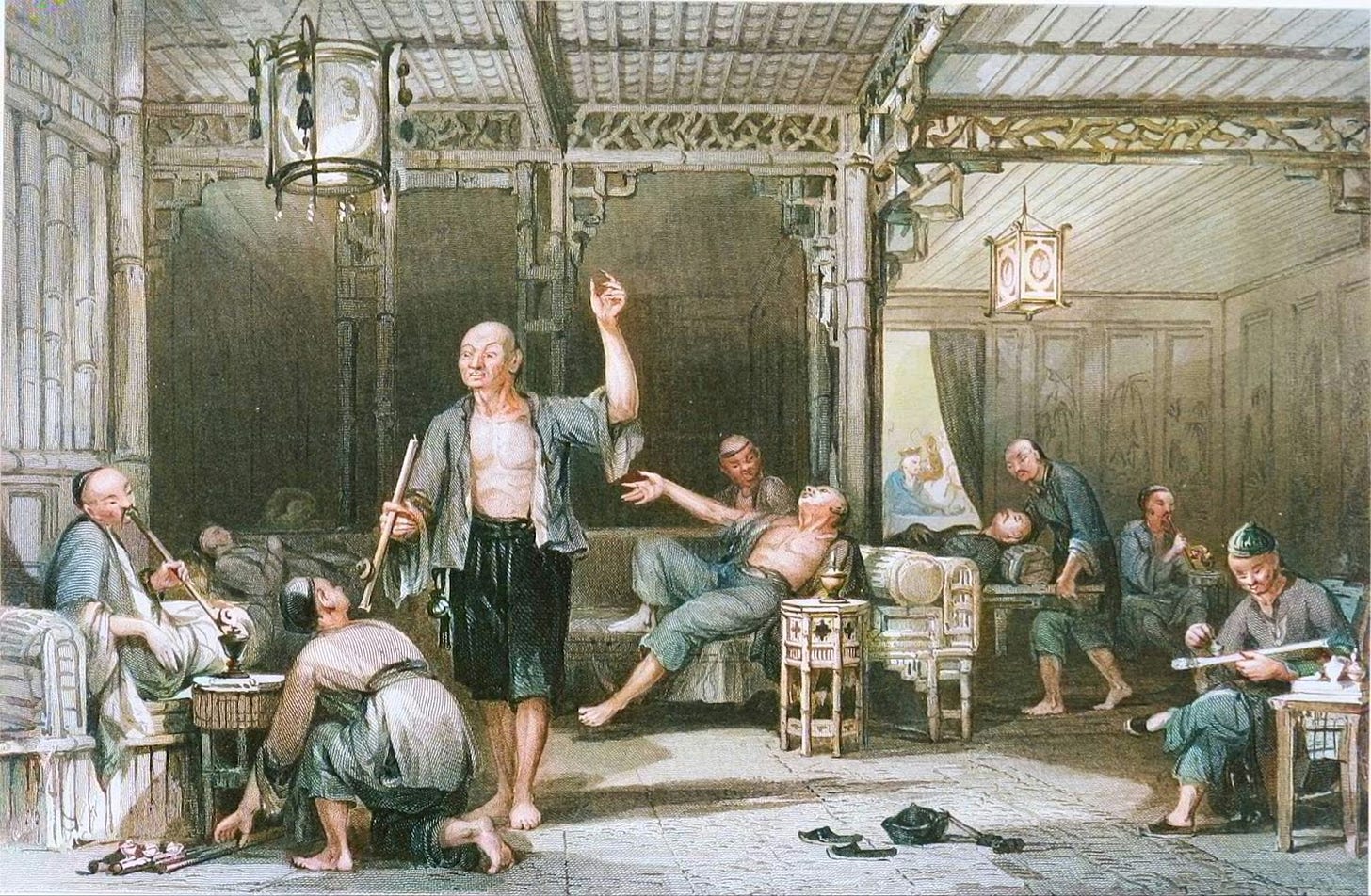

Opium, basically dried latex from the poppy plant, originally hailed from the lands around modern-day Turkey. By the 4th century, it had hitched a ride to China via the legendary Silk Road. There it thrived, grown for centuries and hailed by 11th-century Chinese physicians as a cure-all wonder drug. Trouble, however, was brewing.

Fast-forward to 1715. Britain, ever the opportunistic trader, secured a toehold in the bustling Chinese port of Canton (now Guangzhou). Swapping opium and tobacco for tea, British merchants discovered a lucrative market. Poppy fields in northern British India provided the goods, and demand soared. But as addiction spiraled, the Chinese emperor stepped in. First, in 1729, he banned the sale of opium; by 1799, he had outlawed its import altogether. His message was clear: China wouldn’t succumb to this scourge. But demand? Oh, it only grew stronger.

High-stakes drama: the First Opium War

Opium soon became more than just an addictive commodity. It became dangerous business. Addicts faced execution by strangulation, and traffickers could expect a swift death sentence. Still, smuggling thrived, greased by corrupt officials willing to look the other way for the right price.

Enter Emperor Daoguang in 1839. Determined to reclaim his nation’s dignity, he appointed Lin Zexu, a hardliner vehemently opposed to opium. Commissioner Lin wasted no time: British opium stocks were seized and destroyed, sparking outrage back in London. The British, unfazed, doubled down, sending more opium and forcefully defending their trade routes. The tension boiled over when British sailors killed a Chinese villager and refused to hand them over for trial.

Lin fought back, deploying Chinese ships to attack British forces. It didn’t go well. The British navy, with superior firepower, decimated the Chinese fleet. The emperor, meanwhile, sent letters to London, warning the Brits of their impending doom should they not withdraw. The British response? A blockade of Canton, more ships, and a swift victory.

By 1842, China surrendered. The Treaty of Nanking handed Hong Kong to Britain, opened more ports to British trade, and granted British nationals immunity from Chinese law. Oh, and the Brits had a cheeky suggestion: why not legalise opium and tax it? Emperor Daoguang refused, unwilling to profit from his people’s misery.

Round two: the Second Opium War

But Britain wasn’t done. In 1856, the Second Opium War erupted after a squabble over a British flag on a Chinese ship. Once again, Britain emerged victorious, and by 1858, the Treaty of Tientsin was signed. Though it didn’t name opium outright, China faced mounting pressure to regulate the trade. Ultimately, in the same year, China caved, legalising opium with an 8% import tariff. The emperor found this decision morally repugnant, but resistance had proved futile.

A century of shame

What followed was an explosion in opium use, leaving China debilitated and humiliated. It wasn’t until 1949, under the iron grip of the Communist Party, that the drug was eradicated, thanks to the zero-tolerance policies of Mao’s regime.

The Opium Wars were a turning point in Chinese history, heralding what they call the Century of Humiliation. The mighty Qing Dynasty was humbled by the poppies of British India and the wooden ships of a small European island. It’s a lesson China hasn’t forgotten. Today’s assertive foreign policy? A stark reminder: never again.

Prohibition: America’s noble experiment gone wild

From 1920 to 1933, the United States embarked on a bold experiment: Prohibition. Lawmakers dreamed of solving the nation’s alcohol problem in one fell swoop by banning its sale, production, and transport. Drinking itself? Technically not illegal. At the time, Americans across all social classes were known to enjoy a tipple (or ten), making the whole endeavour a bit of an uphill battle.

A noble idea

With the end of World War I came an idealistic wave of reformers advocating for world peace, moral rearmament, and the betterment of the working class. Puritan reformers envisioned an “age of pure living and thinking,” and alcohol, in their eyes, was a prime culprit behind society’s woes. They decried the drunken breadwinners who squandered their paycheck at the pub, leaving their families in poverty, while alcohol fuelled immorality, violence, illness, and low productivity.

Their relentless campaigning bore fruit with a constitutional amendment banning alcohol: a legal milestone that made alcohol offences federal crimes. This represented a significant shift in American governance. For the first time, the federal government took a direct role in citizens’ daily lives, creating new national police forces and expanding the FBI to enforce the ban. The federal presence became more visible and influential than ever.

From noble vision to chaotic reality

What was meant to be a moral revolution quickly spiralled into a disaster. Prohibition didn’t create a nation of sober, upright citizens; instead, it birthed a sprawling black market and a surge in organised crime. Smugglers and bootleggers stepped in to meet the public’s demand for liquor, and figures like Al Capone built empires on illicit booze.

Cities like New York and Chicago became hotbeds of rebellion, where underground speakeasies flourished, catering to both the working class and the elite. These secret clubs were more than just drinking dens: they became cultural hubs that fueled the rise of jazz, new dance styles, and looser social norms. Prohibition inadvertently ushered in a roaring social revolution.

The brutal reality of enforcement

While the wealthy toasted their martinis in glamorous, hidden bars, working-class neighbourhoods bore the brunt of Prohibition’s enforcement. Raids, arrests, and heavy fines were commonplace, and federal prisons overflowed with offenders. Corrupt officials used their newfound power to punish the poor with alarming arbitrariness, leaving a bitter legacy of inequality.

The era also deepened cultural divides. Protestants were Prohibition’s staunchest supporters, while Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Southern Europe, who viewed drinking as less sinful, opposed the ban. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan exploited the tension, rallying against Catholic immigration under the guise of defending morality. The alcohol ban not only exacerbated class divides but also fanned the flames of xenophobia.

A fitting end to a failed experiment

By the late 1920s, Catholic immigrants were politically ascendant, and the failings of Prohibition were undeniable. Crime was rampant, enforcement costs skyrocketed, and societal divisions grew deeper. With growing public and political support, newly elected President Franklin Roosevelt swept Prohibition aside in 1933 as part of his New Deal, restoring the regulation of alcohol to individual states.

The fact that two-thirds of Congress voted to repeal the constitutional ban showed just how far public opinion had shifted. By 1987, the final vestiges of state-level alcohol prohibition were gone. The lesson? A non-totalitarian government that tells people they can’t drink should prepare for a monumental hangover.

Nixon’s War on Drugs: the never-ending battle

On 21 December, 1970, the ever-stiff President Richard Nixon had an unexpected visitor: none other than Elvis Presley. The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, jetting in unannounced, delivered a handwritten letter to the White House gate. His mission? To offer his services to the president: they both shared an aversion to drugs. Nixon, whose musical tastes leaned more toward Bach than blue suede shoes, begrudgingly agreed to meet. That same afternoon, Elvis walked out of the Oval Office as an honorary agent for the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, armed with a shiny badge and big plans for his anti-drug campaign, Get High on Life. Seven years later, Elvis himself would succumb to an overdose.

From fringe to full-blown crisis

Elvis wasn’t wrong to be worried. Until the 1960s, drug use in the West was mostly confined to the fringes: immigrant communities preserving old traditions, bohemian artists chasing inspiration, and upper-class types discreetly dosing on doctor-prescribed opiates and amphetamines.

Famous historical junkies

Opium: Jean Cocteau, Aleister Crowley, Aubrey Beardsley, Jan Jacob Slauerhoff

Heroin: Edith Piaf, Amedeo Modigliani, Judy Garland

Cannabis: Victor Hugo, Gustave Flaubert, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire

Cocaine: Koning Vittorio Emanuele III van Italië, Sigmund Freud, Walter Benjamin, Marcel Proust, Frida Kahlo, Nancy Mitford

Amphetamines: Adolf Hitler, koningin Wilhelmina van Nederland, Erwin Rommel, Heinrich Böll, Winston Churchill (vermoedelijk), Graham Greene, Jack Kerouac, John F. Kennedy

But the swinging ‘60s changed all that. Cannabis became the counterculture’s recreational drug of choice, embraced by students and hippies as a symbol of rebellion. Meanwhile, thousands of soldiers returned home from Vietnam with a heroin habit, bringing addiction into American living rooms. With imports ramping up to meet demand, drugs began to devastate Black communities in major cities. What was once a fringe issue now loomed as a national crisis.

The birth of the War on Drugs

Nixon, ever the puritanical pragmatist (with a healthy dose of disdain for both left-wing hippies and African Americans), decided enough was enough. In 1971, he launched the War on Drugs. At first, the campaign focused on prevention and treatment, but it quickly pivoted to a more aggressive stance. Billions were poured into law enforcement, and U.S. forces intervened in no fewer than 59 countries to suppress drug trade and production. The public was all in. By 1969, a staggering 84 percent of Americans supported jailing anyone caught with even a small amount of marijuana.

A war with no end

Fast forward 50 years, and Nixon’s War on Drugs has become an expensive, enduring debacle. With thousands of federal agents, a multi-billion-dollar budget, and a sprawling global enforcement network, the U.S. has spent over $1 trillion trying to win this war. The results? Let’s just say no one’s celebrating.

More than 2 million Americans are incarcerated, giving the U.S. one of the world’s highest imprisonment rates. Over a quarter of these inmates are serving sentences for drug-related crimes, and many more for offences indirectly tied to drug use. Instead of shrinking, the global drug trade has ballooned. Cannabis production has increased tenfold since Nixon’s declaration, while heroin and cocaine output has skyrocketed twentyfold. And that’s not even counting the meteoric rise of synthetic drugs like methamphetamine.

What have we learned?

After five decades and a trillion dollars, the War on Drugs has achieved little beyond overcrowded prisons, devastated communities, and a thriving global drug trade. The United States is not alone in suffering the fallout. Its policies have rippled across the world, fueling corruption and violence wherever drug markets thrive.

So, is there a better way forward? In the following, we’ll explore alternatives. And yes, it has everything to do with the idea of tolerance. Stay tuned.

Forbidden fruits

The cost of fighting vs. taxing drugs

When people do things we disapprove of, society has two tools at its disposal: tax them or punish them. But when you think about it, they’re really two sides of the same coin. Taxes make things more expensive, and punishment operates similarly: the likelihood of getting caught, multiplied by the severity of the penalty, effectively increases the “price” of the activity.

This dynamic is glaringly obvious in the drug trade. Dealers and manufacturers take enormous risks, often working under extreme pressure. Imprisonment is almost a given for those lower down the supply chain. Yet they accept this as a calculated cost of doing business, and that cost is passed directly onto the consumer.

Lessons from alcohol and tobacco

For legal substances like alcohol, taxes demonstrate how pricing can regulate behaviour without collapsing into chaos. In Europe, about 50% of the retail price of alcohol is tax, doubling what retailers receive. But this moderate tax hasn’t spawned much of an illegal market. Sure, a bit of smuggling and home brewing exists, but nothing that undermines society.

Contrast that with cigarettes, where taxes have come to account for about 75% of the price in Europe. That’s where things get dicey: tobacco smuggling has made a noticeable comeback. The lesson? Push taxes too high, and you’ll find yourself fueling crime.

The price of cocaine: a case study

If cocaine were legalised and untaxed, estimates suggest it would cost around €2 to €5 per gram. Compare that to its current street price of €50 to €100 per gram — a markup of around 2,000%. Even a modest tax on legal cocaine would make crime less appealing. But at current black-market prices, drug dealers are practically printing money. High taxes — or outright prohibition — don’t just fail to stop crime; they make it wildly profitable.

The problem with fighting crime

The difference between €2 and €50 per gram isn’t going to schools or hospitals. Instead, it vanishes into the pockets of criminal organisations, fueling their growth. This money creates sprawling, international networks that are almost impossible to dismantle. Like the Hydra of Greek mythology, cutting off one head just causes another to sprout.

Despite military raids, takedowns of major cartels, and even overthrowing governments, the global drug trade hasn’t skipped a beat. Over the last 50 years, the production of drugs like cocaine and heroin has soared. And with current methods, the Hydra isn’t going anywhere.

A change in strategy

It’s time to face the obvious. Fighting drugs head-on has failed. Instead of sinking billions into this endless war, we should focus on regulating drugs. But legalisation isn’t without its pitfalls, and critics of the idea aren’t necessarily simpletons. Their objections — some valid — deserve to be addressed thoughtfully. It’s time to rethink the rules of the game.

The disadvantages of drugs

Separating fact from fear

Let’s start by debunking a major myth: most drug use isn’t inherently problematic. The majority of people who occasionally pop a pill, smoke a joint, or take a bump don’t suffer adverse effects and aren’t addicted. In fact, this applies to roughly 80 percent of users. The percentage varies slightly by drug, of course. About 10 percent of cannabis users experience issues, while 30 percent of crack and heroin users face serious problems. The risks? Addiction, health damage, and behavioural changes.

But much of the danger lies in the illegality of drugs. They’re expensive. You can’t buy them legally, forcing users into contact with criminals. And because illicit drugs are often impure, dosing mistakes and health problems are common. If we’re discussing legalisation, we can set these factors aside. They’re problems born of prohibition, not the drugs themselves.

Does legalisation mean more use?

Legalising drugs comes with undeniable benefits, but it’s not without drawbacks. The biggest concern? Removing legal barriers would likely lead to increased use. With prices dropping and availability rising, more people might try drugs, and current users could indulge more. Predicting the extent of this increase is tricky; no modern nation has fully decriminalised all drugs.

Some countries, however, have dabbled in partial legalisation:

Canada legalised cannabis in 2018, and usage rose by about 50% in the lead-up to legalisation. Since then, it hasn’t declined.

Portugal decriminalised the use of all drugs in 2001, though trafficking remains illegal. Drug use has increased slightly but remains below the European average.

In the Netherlands, where cannabis use has been tolerated since 1976, usage has doubled, but so has use in neighbouring countries where cannabis remains illegal. Dutch rates are not significantly higher than elsewhere.

Without precedents for full legalisation, we can’t predict its exact effects. However, it’s safe to assume an increase in use, with more people under the influence, higher addiction rates, and potentially greater health damage. The worst-case scenario? A descent into chaos, like opium in 19th-century China or alcohol in the early 20th century, where large swathes of the population became too intoxicated to function, creating social and economic devastation. Young men, especially those facing unemployment or lack of prospects, would likely be most at risk.

The upsides: a different perspective

On the flip side, legalisation could dramatically reduce deaths from violence and overdoses. The burden on police, courts, and prisons would plummet, and countries could escape the grip of illegal drug markets. Without financial pressure from exorbitant black-market prices, problem users could afford their addictions and medical treatment. Many would avoid homelessness and might even hold onto their jobs.

Legalisation would also unlock massive resources. Tax revenues and savings from crime enforcement could be redirected to health care, education, and addiction treatment. Crime rates? Likely to nosedive. Some opponents argue that criminals would simply shift to other illegal markets, but that’s a stretch. Without lucrative black markets, there’s little incentive for mafias to conjure up demand for, say, counterfeit goods or human trafficking.

The bigger picture

Legalisation isn’t without risks, but it offers a compelling alternative to the disastrous war on drugs. Yes, more people might use, but the savings in lives, resources, and societal stability could outweigh the costs. The key lies in careful regulation, thoughtful implementation, and an honest conversation about what’s at stake. After all, the current system isn’t just broken. It’s making things worse.

A drug ban is paternalism

The debate around drug bans isn’t just about crime or public health. It raises profound philosophical questions. If someone chooses to use cocaine, can society justifiably force them not to? Let’s consult the thinkers.

John Stuart Mill’s harm principle offers one answer. In short: coercion is only justified to prevent harm to others, not harm to oneself. If using cocaine primarily harms the user — even if that user is one of the 20% who develops a serious addiction — then it’s their choice. Collateral harm to others, like strained relationships or missed work, isn’t enough for Mill to support a ban.

But Joel Feinberg added nuance. He argued that you must consider whether coercion ultimately creates more freedom or less. Yes, legalisation might lead to a slight increase in addiction, but only a fraction of the population is likely to start using drugs, and an even smaller fraction will develop serious problems. Meanwhile, a much larger group — the curious, the occasional users, and the already addicted — gains significant freedom. They could partake openly, without fear of arrest, while society as a whole would benefit from dramatically reduced crime rates. The net result? Legalisation increases freedom.

What about risk awareness?

Mill also argued for what’s called soft paternalism: using coercion when people are unaware of the risks they’re taking. And let’s face it, no one snorting their first line of cocaine expects to become one of the 20% of problem users. Mill’s analogy? Stopping someone from crossing a dangerous bridge they don’t realise is unsafe. But once they understand the risks, they’re free to cross.

Applied to drugs, this means we must ensure users are fully informed. A leaflet or warning label? Too easy to ignore. A brief chat with a doctor or a pharmacist? Too fleeting. What we need is something more robust.

Soft paternalism in action: the drug certificate

Here’s a radical idea: a drug certificate. Before buying any drug, users would have to pass an exam proving they understand its effects, risks, and alternatives. Pass the test, and you earn a stamp in your drug passport, granting you access to that substance. Fail? No drugs for you, at least not legally.

Controlled sales and pricing

Drugs would only be sold at regulated outlets — pharmacies, for example. Letting free-market retailers handle distribution is a terrible idea, especially in the early days of legalisation. The profit-driven retail sector would push sales through aggressive advertising and marketing, which we definitely don’t want. Instead, a monopoly of regulated outlets ensures:

Strict quality control: No more dodgy batches or dangerous contaminants.

Proper checks: No drugs passport, no purchase.

As for pricing, taxes can deter overuse without driving the trade underground. History indicates that a 100% tax is about the maximum you can charge without inviting black-market competition.

Dealing with problematic use

Let’s not kid ourselves: some people will develop addictions. Ten to thirty percent of users may need treatment or other interventions, and society must be prepared to address the fallout. But relying on the government to handle this? Not ideal. Bureaucracies are notoriously inefficient, and the state already has plenty on its plate.

Instead, every drug passport holder could be required to join a user organisation. These organisations — whether addiction treatment centres, insurance providers, or even trade unions or religious groups — would be funded by the tax markup on drug sales. In return, they’d:

Monitor and guide users: preventing occasional use from becoming problematic.

Treat addiction: offering services to help users who develop dependency.

Provide compensation: covering damages caused by problem users.

A wild idea worth trying

Sure, this might sound like something out of a sci-fi novel, but why not experiment? Start small: one drug, one region, one trial. If it works, scale up. If it doesn’t, tweak the system. The current approach has been a catastrophic failure, inflicting massive social harm while solving nothing. It’s time to stop clinging to outdated policies and start exploring real solutions.

To conclude

I planned to write an article about crime and punishment in this series on freedom and coercion. But gradually I realised that the drug problem is such a major factor that it warrants a separate article. Moreover, we have now turned to a practical application of the harm principle and soft paternalism, which were discussed in the previous episodes. Next time it'll be about crime and punishment, I promise.

For further reading

William McAllister, Drug diplomacy in the Twentieth Century. An international history (2000)

Jeffrey Miron, Chris Feige, The opium wars, opium legalization, and opium consumption in China, National Bureau of Economic Research (2005)

Zheng Yangwen, The social life of opium in China (2005)

Mark Kleiman c.s., Drugs and drugs policy. What everyone needs to know (2011)

Julia Lovell, The opium war: drugs, dreams and the making of China (2011)

Lisa McGirr, The war on alcohol. Prohibition and the rise of the American state (2015)

Johann Hari, Chasing the scream: the first and last days of the war on drugs (2015)

David Farber (ed.), The war on drugs. A history (2022)

This was the sixth article in the series on liberty and coercion. The next article will be published in two weeks, and will be about crime and punishment.