The Korean village known for its magnanimity

How a South Korean village drifted into modernity in one generation. About 'insim', individualisation and melancholy. This article is the introduction to the series on freedom and toleration.

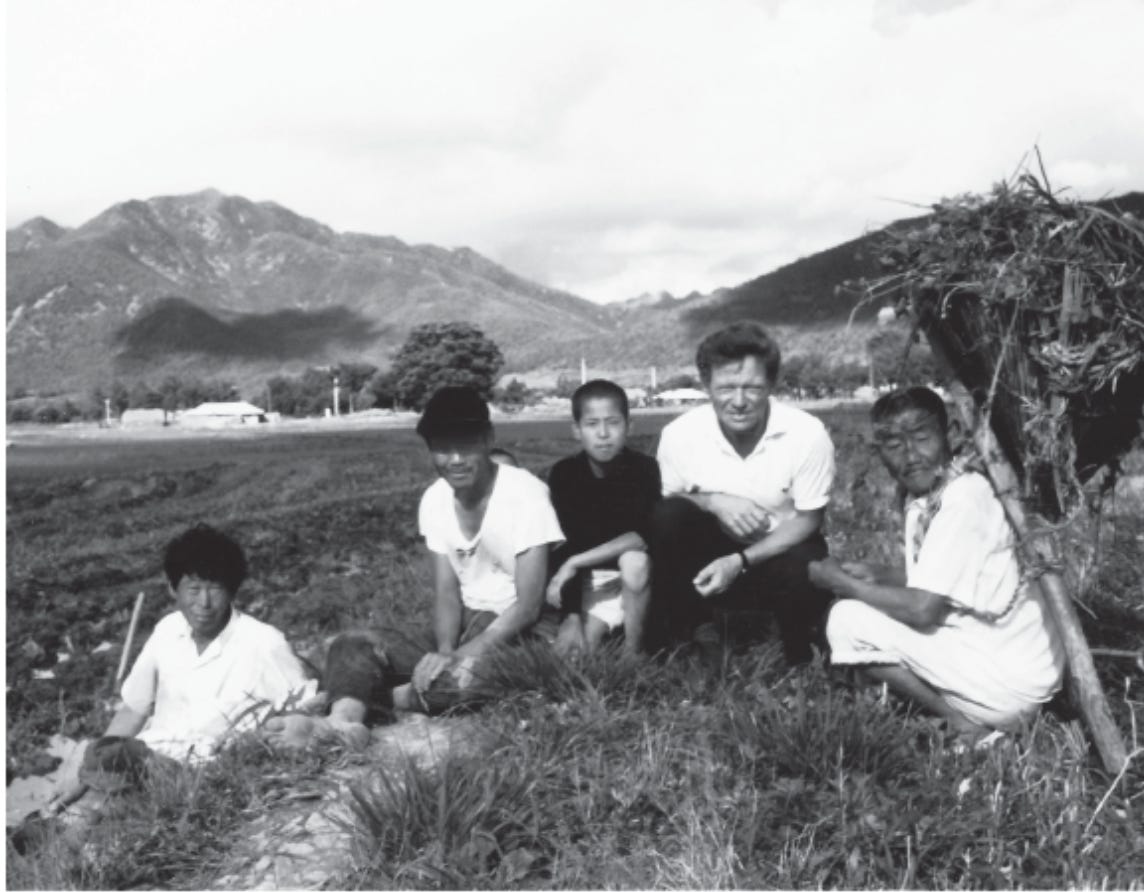

In 1992, the anthropologist Vincent Brandt (b. 1924) wanders through the South Korean village Uihang, on a remote peninsula on the west coast. He finds the overgrown memorial stone with his name on it, from 1966. He then stayed there for a year for field research, for which he obtained his PhD. Brandt walks around a bit confused. In 1966 he was a well-known figure in the village. Everyone knew him, and he knew everyone. His memories from 1966 read as a succession of community spirit and hospitality. Wherever he walked, he was called in for endless chatter and drinking parties. Twenty-six years later, he is recognised here and there, but most residents no longer have time for him. The poverty of the village had given way to hard, well-paid work. Oyster farming and octopus catching, a marginal activity at the time, city dwellers now pay big money for. Rice cultivation was what fed the village at the time. Well-to-do aristocratic farmers had several acres of rice field; most peasants had only a fraction of that. It was barely possible to live on that. Now a part of the bay had been reclaimed, covered with rice fields. That was hard work, but the price of rice had plummeted. A Christian church had appeared; half the village had now become Christian. In 1966 no one was Christian: Confucianism was dominant. Temples and even ancestral shrines were now deserted. Everything now revolved around money, but no one had time anymore.

In 1966, Brandt had made an unorthodox choice. Instead of the anthropological fashions of the time, he started researching the pre-modern moral culture of the poverty-stricken Korean village, which was on the verge of disappearing. Korea has rocketed into modernity over the past fifty years, from a poor developing country to one of the most advanced economies in the world. Brandt's analysis from 1966 fits seamlessly with the universal human moral modules which I described earlier. You can still see pre-modern morality in all its glory.

The premodernity of a village in South Korea

Kin selection

The village had about 700 inhabitants, divided into more than a hundred households, consisting of two large clans and a handful of smaller ones.

The somewhat stiff, conservative Yis could make a reasonable living from it. Most lived mainly in two quiet hamlets on the south side of the bay. They earned their income mainly from rice cultivation; they had the largest lands. Genealogy played a major role in Confucian culture: everyone knew their family tree like the back of their hand. The noble Yis were descended from king Taejong’s twelfth son (1400–1418) and they were proud of it.

There were more of the Kims. They lived across the bay, near the harbour, where most of them fished on small sailing boats without an engine. Fishing was considered dangerous and adventurous: if you had a good catch, your ship had come in. But you rarely had a good catch, and the chance of a watery grave was considerable. It was lively around the harbour, there was constant shouting, swearing and drinking. The Kims were much poorer; the Yis thought they were vulgar, and everybody knew that the Kims had collaborated with North Korea during the war.

Family is central to Confucianism. Ancestors have their own temple where an annual memorial service takes place. The authority of the parents is undisputed. The older you are, the more respect people owe you. Rebelling against your parents is about the worst thing you could do. Morally speaking, it would be better to commit theft or murder. Everyone in the village was aware of the genealogical relationships in detail. Loyalty to one's own family members came above all else. If they could only somewhat afford it, investments were made above all in the children's education. For the head of the family, the growth of the family capital was always paramount.

Reciprocity and retribution

When Brandt arrived in the village in 1966, he was extremely wealthy by local standards, thanks to his American salary. For the first few weeks he stayed with the village teacher, where he was cared for based on the laws of hospitality, which were taken very seriously there.

He then bought a small piece of land on a hill above the harbour, where he built a modest house. Then he encountered a problem: although he had no shortage of banknotes, no one wanted to sell him food. Fishermen hid their fish in the boat, saying they had already sold out. Farmers came up with excuses. Money only played a role in the local economy in large transactions, such as the purchase of a boat or a piece of land. For daily needs, such as food, you had to rely on your network. Give a little, take a little. Everyone in the community appeared to be continuously aware of the mutual accounting of service and return. If you had an outstanding debt, repayment was a matter of reasonableness. Pay back when it suits you. Nonetheless, there were regular arguments about outstanding debts and repayment. But that constant friction was also part of the social dynamic of the village. There were constant interactions between all and sundry.

Not that you never had to pay back. Land sometimes changed ownership because the owner needed to clear debts. If, with the best will in the world, someone could no longer pay their debts, leaving the village, quietly, was the only solution.

The exchange rate was reputation. If you were known as a miser or a spendthrift, someone who does not fulfil his obligations, or who always argues about service and return, it was more difficult for you to get things done when you needed help, and you had less influence in village affairs.

Ultimately, Brandt managed to gain the necessary goodwill by expanding his network and by having access to an extensive medicine cabinet and bottles of whiskey. He never asked for money, but all gifts were remembered. This also applied to manual services, such as help with fishing or harvesting, or with renovations. And those who sat down on Brandt's veranda were lavishly served with food and drinks. That's how you made friends.

The downside of this fairness was dealing with crimes and transgressive behaviour. The police were very rarely called in. The village solved them among themselves. There was no shame in meddling; privacy hardly existed. If you noticed that your neighbours or family members were arguing or getting stuck on something, it was considered a virtue to intervene, mediate or give advice. Mind your own business, we would say, but in Uihang they thought differently.

Misconduct was generally covered with the cloak of charity, but one could also go too far. Anyone who found themselves being ostracised by the community could only do two things. Self-chosen isolation was not the most attractive option. No one was self-sufficient, and if no one wanted to talk to you or exchange goods or services with you, then you had no life. The only way out was to leave the village. Taking refuge in a nearby village was usually not an option. Such newcomers were treated with suspicion, and your reputation would follow you. Moving to the city was actually the only option. A marginal, anonymous existence probably awaited you there.

Hierarchy

In addition to reputation, your place in the hierarchy also played an important role. The village chief and the schoolmaster, both from the Yi clan, were held in highest regard, together with the leader of that clan and the richest man in the village, and then the most important family head of each of the six hamlets. If one had completed secondary education, one would of course also have bonus points, and the higher the age, the higher the status. Titles of address and the depth of your bow reflected your place in the hierarchy. Those higher in rank were allowed to sternly address lower ones, but certainly not the other way around. Moreover, your status determined who you could be friendly with.

When Brandt arrived in the village, his status was not immediately clear. He worked at a university, and that gave him a high status, he was already forty-two, he had money to burn, and friends among the elite of Seoul, but he wanted to be on an equal footing with everyone, clumsily helped with the humblest jobs, also hung out with the poorest slobs, spoke clumsy Korean and lived in a modest house on the 'wrong side of the bay'. Eventually the solution was found: he was given the same title as that of his host and friend, the teacher, and was allowed to address everyone as if he were from the Yi dynasty, as the teacher's 'brother'.

Leadership was hardly visible in the village. The village head was mainly a mediator between the hamlets and families on the one hand, and the government on the other. Decision-making in the village was never a matter of power or force, but rather of mediation in back rooms with influential men. As a result, decisive action was rarely taken as long as there was no consensus yet.

Several informants specifically praised the village head be- cause he did not try to impose his ideas too forcefully. He has enormous prestige in the village for his moderation, honesty, and concern for proper behavior, but he uses his influence in an indirect manner. He is a moderator rather than a leader and is careful not to risk his popularity by driving too hard to achieve specific goals that would excite immediate and strong opposition.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Also in team efforts, trying to rule the roost wasn’t appreciated. On a fishing boat, the skipper was a cooperative foreman who rarely gave orders, and even then he was not always listened to.

We went a couple of miles across the bay to pick up a friend of the captain's before leaving for Inchon. (...) Soon we were aground in the mud. There was a lot of poling and shouting from the bow and a great deal of starting, stopping, and reversing of the propeller as we hunted for a channel that would take us right up to the rocks. Changes of course, plan, and even helmsman took place rapidly without any apparent coordination, all accompanied by a constant stream of shouted warnings from the bow and insistent suggestions from everyone else. Judged by New England standards the atmosphere on the boat was one of chaotic excitement border- ing on panic.

Throughout the episode, however, nothing occurred that really upset the skipper or crew, or that even seemed noteworthy enough for them to talk about afterwards. No serious mistake in seamanship was made, and the boat was worked reasonably effectively. There was no visible evidence of the captain being in command except that he held the tiller more than anyone else. Everyone seemed to operate independently according to his own whim, and yet it all fit together somehow to produce the desired result. When we finally did get near the rocks and located our passenger, the boat handling was impressive. Considerable surge of the sea and jagged half- submerged rocks made it a nasty spot. I still don't know if the captain's impassivity amidst pandemonium was fatalism or expert knowledge of the "landing."

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

It was the same when building a house. Through the eyes of an outsider, the collaboration was chaotic, with a lot of shouting and arguing. But miraculously, everyone did what they had to do, and it always ended well. The gentlemen farmers also had to act tactfully towards their employees. Whoever tried lording it, would be criticised behind his back — bad for your reputation.

Collaboration within the group

The village was remote, on a peninsula where the road ends. It was considered poor and backward in the region. That may be so, the residents said, but at least we have insim. Everyone could agree on that. Insim is a difficult word to translate. I would call it magnanimity. Brandt describes it as maintaining good relationships with others, with a degree of warmth and goodwill. Conflicts and violations of standards occurred every day, but they were rarely fought out at the sharp end. The seven hundred inhabitants had to rely on each other for generations. Feuds would have had a devastating effect. One’s reputation was ruined if one were known as a cheater, alcoholic, adulterer or troublemaker, but even then you could still get along with your fellow villagers.

Villagers showed enormous tolerance for the failings of others. Although critical gossip about specific acts was normal, it was rare to hear someone being judged or categorized in absolute moralistic terms. While there were plenty of brief, explosive, emotional outbursts, such antisocial acts were regarded as temporary lapses rather than as an indication of evil nature. Everyone is eager to make allowances, find excuses, and encourage the person responsible to resume normal behavior. There is a concerted effort, in which even the participants eventually join, to smooth over the break and restore harmony — or the appearance of harmony. Also, from the point of view of the individual participant in a quarrel, holding a grudge is really a kind of self-punishment, since one of the main recreations of villagers is the pleasure they take in one another's company.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

But one could also go overboard. In the most extreme cases individuals were excluded:

A man with a bad reputation, who is neither liked nor respected, easily joins groups without apparent discrimination and participates in the general cordiality. On the rare occasions when a decision is made to turn against someone and have nothing to do with him ("Let us all refuse to cooperate"; Ilch'e hyopcho haji mara) it is done jointly, and enforced, by an entire clan or by the village as a whole.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Because the village actually had too little agricultural land and there was too little capital to invest, not everyone was always working hard. Outside of harvest time, there was also plenty of time for chatting with the neighbours during the week. It took no effort if one looked for a chat. And neighbours also often came to each other’s doors. If Brandt didn't feel like socialising, he had to leave the house, go to the beach or into the hills, actively avoiding bumping into someone.

The disadvantage of the solidified relationships and the weight of tradition was that innovation in the village hardly got off the ground. The men who carried the most weight were those who had the most land and actually lacked little. The poorer villagers simply had no money to invest. Moreover, zero-sum thinking was the norm in the village: the idea of the win-win of cooperation was not in their minds. In the eyes of the villagers, progress had nothing to do with individual efforts. Progress just happens, like luck. Education was highly regarded, but years of study of Confucian wisdom was on the same level as practical technical training. Success in business was of course never begrudged, but the highest attainable goal was a position in public administration. The village was most proud of the farmer's son who had become police chief of the region.

Individualism was not appreciated in the village. If you isolated yourself or did you not care about the expectations of your family, you could count on severe criticism. In addition to your behaviour, your identity was mainly determined by the role you had in the community: your family, your profession, where you lived, and the behaviour of your family members.

Under cover of apparent conformity with collective norms most individuals are constantly promoting their own interests, and the prevailing tolerance permits someone who is both ruthless and thick-skinned to do some outrageous things. But there is a limit beyond which a man cannot go and still participate fully in village social life. The amassing of personal wealth in itself, particularly if it appears to be at the expense of one's fellow villagers, does not bring rewards in terms of higher status. On the contrary, it can lead to suspicion, censure, and even isolation. (...) Demands for hospitality, generosity, the proper observance of ceremonial obligations to kin, and assistance to neighbors still usually have precedence over the profit motive in determining behavior.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Ownership and redistribution

Not everyone in the village had a field or a boat. About twenty percent of the population had at most a small garden with home grown vegetables. In the spring, when winter supplies were exhausted, they really suffered from hunger. They survived with what they could gather in the hills and on the coast. Relatives and neighbours in the village helped to keep them alive, but when last year's harvest was disappointing, that help also fell short. The poorest people in the village then had to rely on distant relatives in surrounding villages, a few hours' walk away. During that period, the poorest travelled through the region begging. No one died of hunger, but the situation was often limited and infant mortality was high. And anyone who had to rely on such charity was of course indebted to their family and neighbours, who were also not well off.

In a village with so much poverty, things were occasionally stolen. Petty theft was generally ignored or — even against one's better judgement — attributed to children. Everyone knew that dire poverty occurred, and incidents were turned a blind eye.

Poaching by boys and young men of poor families occur(s) now and then. The areas of sand and rock enclosed in stone fish traps are considered private property, and netting fish or digging for octopus there when the tide is out is regarded as a serious offense. On the other hand, the owner understands the family circumstances of the offender and knows he would not be there if there was enough food in his family. A monumental bawling out is the usual punishment, but repeated offenses damage a boy's reputation — and that of his family.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Zero tolerance would strain mutual relations too much. Leniency was the norm. But villagers could also go overboard. In cases of grand theft, sorcery was employed. The victim caught a weatherfish. On the birthday of the alleged thief, the animal's eye was gouged out while an appropriate incantation was uttered. Then the thief would become blind. Two people in the village had been struck with blindness. Serious theft was therefore rare. Only one case is recorded in which a thief was expelled from the village. Even in a case of manslaughter — a clash between two fishermen that got out of hand — the perpetrator was welcomed back in the village after serving his sentence.

Empathy and compassion

As mentioned, the poorest ones could always rely on their family and neighbours in difficult times. Unfortunate cases were also taken care of. A man who had a serious accident on a fishing boat was then helped by his family to work on a farm. Two residents were crippled: both ran a small drink shop thanks to their family. The poorest woman in the village was a widow with children but virtually no family ties in the village. Every now and then her neighbours gave her something, but without much pleasure.

Freedom versus group interest

Why such a long introduction about an insignificant Korean village more than fifty years ago? To outline where we come from: the non-modern community. To see what mechanisms operate in communities around the world when individual expression and interests conflict with the interests and values of the community.

The anthropologist Oliver Scott Curry, who I mentioned earlier, argues that our biological morality is motivated by an ingrained urge to work together at the community level.

Selfishness and kin selection coincide. We are programmed to pass on our genes under the most favourable conditions possible.

Because we originally live in groups with which we mainly share our genes, the importance of our own group is a derivative of self-interest and kin selection. Our own group competes with other groups. Because of our ingrained tendency towards zero-sum thinking, a loss for the out-group means a gain for our own in-group.

The other elements of Curry’s morality-as-cooperation are a derivative of these principles:

Reciprocity and retribution. People who help us or our group are our friends, we in turn help them and we trust them. People who go against our own self-interest and group interest are punished.

Bravery. People who take risks for the group are highly respected.

Respect. Those who sacrifice themselves for the group interest, follow orders, and respect people with more status or authority, are rewarded.

Fairness and compassion. We have to stay out of each other’s hairs sometimes. Conflicts are not fought out on the razor's edge, we also have to grant each other something, be able to make compromises and forgive mistakes.

Property must be respected. Theft is punished and harm must be compensated.

The list is not without controversy. I would definitely want to add hierarchy, and a degree of redistribution within the group. But the essence is clear. Our innate morality is (primarily) focused on kin selection and collaboration within the group.

But the modules can collide. Self-interest and group interest in particular often conflict with each other. Let me give another example from Brandt's book.

A narrow sandspit, connecting the main part of the village to the rest of the peninsula, faces the Yellow Sea on one side and a bay (or mudflats when the tide is out) on the other. As a part of the effort to reclaim tidal land for rice agriculture, grass and small trees were planted on the sand dunes, both in order to strengthen them as a barrier against the ocean and to keep sand from blowing onto the proposed rice fields. As soon as the grass really took hold, a nearby farmer staked his ox on the dunes every day in order to take advantage of the free fodder. He persisted in spite of a few protests, including that of the village head.

— Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Here the freedom of the farmer was at stake. He could graze his ox wherever he wanted, but not on that narrow spit of land. The vegetation on that headland was in the interest of the entire community. Group interest took precedence over his self-interest.

Self-interest can conflict with the above-mentioned moral modules in many ways. If you helped me move, and I don't return the favour when you need my help, then you are right to be disappointed. If you run away when your friends get into a bar fight, your friends will think you're a coward. If I don't stand up on the subway for someone who is visibly having trouble standing, then I'm behaving like a lout. If I immediately demand repayment of a debt from someone who clearly cannot pay it immediately, I am behaving like a jerk. If I take an ice cream from the freezer of a store without paying, then I am a thief. In short: even if you have the freedom, there are certain things that you cannot do with impunity, in which group interests take precedence over self-interest.

Modernisation at rapid speed

Back to Korea, to the village of Uihang, which Brandt calls Sŏkp'o in his books. What happened there in the twenty-six years between Brandt's visit in 1966 and his return in 1992? In short: modernisation happened.

"We live better, we eat better, we can get medical attention when we need it, and our young people come and go as they please and marry whom they please. We go to T'aean and Sŏsan all the time, both for business reasons and to see friends and relatives. Sŏkp'o is just a place where people own land and houses.”

I say, “All that sounds like the kind of development that everyone has wanted all along. What are the bad things that have happened?” Yi Pyŏngun answers this time with more emotion.

“There is nothing secure and permanent in our lives the way there used to be. We can't depend on our relatives and friends when we need help, only on the money we earn. People will do anything for money. When I was young we learned that the most precious thing was the land our ancestors handed down to us—that it was the whole basis of our family's reputation and prosperity, and that we must preserve it above all other things. But now, the land no longer pays, even to grow rice. We don't need the trees anymore on our mountain land for firewood or to build our houses and boats. So my cousins sell their land to rich people from the city, even when it has their ancestors’ tombs on it!”

Vincent Brandt, An affair with Korea: Memories of South Korea in the 1960s (2014)

This new series is about freedom. In the quote above you see that within one generation the residents were given the freedom to marry whoever they wanted, instead of being married off. It is just one illustration of how modernisation was accompanied by more freedom. But modernisation meant more, much more. Developed in Europe, modernisation spread like wildfire across the world. It was an attractive model because it brought economic progress and therefore prosperity, and more individual freedom. It also ended up in South Korea via the United States.

I explained in an earlier article what the modernisation of Europe entailed. Almost all elements are intertwined with individual freedom:

Secularisation. Faith was less naturally experienced collectively; it became an individual choice.

Separation of church and state. Religion became less influential. Legislation, i.e. coercion, was stripped of religious elements. Religious morality was no longer imposed from above.

Individualisation and egalitarianism. As individuals we could look after our own needs, we became less dependent on the collective. At the same time, we were recognised as equal individuals in society: the government started treating us indiscriminately.

From community to society. People went through life more anonymously, ties became more superficial. We became less dependent on others.

Nation states and nationalism. Regionalism faded into the background; national bureaucracies emerged. The hold of the nation state became stronger and more effective.

Constitutional democracy. Instead of an organic government based on consensus, a born elite or the whims of a local potentate, everyone now had an equal voice, at least formally.

Human rights, freedom and equality, ideology. The tension between freedom and equality was now anchored in rights and ideology. Governance became tied to the rights of the individual.

Globalisation and mass media. The view of the world became broader: more and more information became available, communication became faster, allowing individuals to form their own opinions.

The Scientific Revolution. Technological innovation gained momentum, leading to greater prosperity, making individuals less dependent on the community.

Commodification. Zero-sum thinking was replaced by win-win thinking. Growth became the norm, instead of stability. Those who took opportunities could become much richer than was conceivable in a traditional society. Industrialisation set a flywheel in motion, allowing more people to afford goods. The working population became increasingly better educated.

Modernity is a difficult concept to define. Although I stick to my own description, the video below offers an interesting yet slightly different interpretation of modernity.

The next episodes

In non-modern communities like those in Uihang, there may not have been a great deal of freedom, but there was tolerance. Perhaps not the same tolerance we are used to, but rather a form of magnanimity. Reputation was everything. Misbehaviour did come at the expense of your reputation, but the ultimate sanction, expulsion, was rare. Even after misbehaviour, villagers could still function well in the community. People understood each other's missteps.

It reminds us of Erasmus's mildness: people can err, we all make mistakes, we have to help each other, people are not black and white. Even if we disagree, we don't have to immediately condemn each other. Take a sip, make a joke, and remain good friends.

This new series is about freedom and tolerance. How do we deal with people who transgress standards? Modernity has specific solutions for this, often of a legal nature. Human rights. The harm principle. Criminal law. These solutions will certainly be discussed in this series.

The downsides of non-modern magnanimity were great: narrow-minded morality, irrational popular belief, fatalism, zero-sum thinking, low prosperity and no growth, deep poverty, no privacy, a class society with unequal opportunities.

But it is not without reason that reading Brandt's books makes us feel melancholic. If only we still had insim: community spirit, conviviality, magnanimity, trust, selflessness, reasonableness.

There is no escaping modernity. There is no way back. Nor should we want to. But is there perhaps a way forward, to a society that knows how to combine the best of both worlds? That will be the central question in this series. Can we retain the achievements of modern society and at the same time regain a tolerance that is not based on regulation and distrust, but rather on trust, community spirit, respect and magnanimity?

I haven't got all the episodes in this series completely in view yet, but I think the following themes will be addressed:

Individualism

Trust

Paternalism

Criminal law

On free will and how to influence it

Autonomy

For further reading

Vincent Brandt, A Korean village: Between farm and sea (1971)

Vincent Brandt, An affair with Korea: Memories of South Korea in the 1960s (2014)

Oliver Scott Curry c.s., Is it good to cooperate? Testing the theory of morality-as-cooperation in 60 societies, Current Anthropology (2019)

This was the first article about freedom and toleration. The next article will be about individualism.