What’s so bad about polarisation, really?

What's the state of polarisation in Europe? We'll discuss the pros and cons, risks, elite influence, and the societal and democratic impact.

Do you find yourself fretting about polarisation? People seem less and less willing to tolerate opposing views. Public debate feels angrier than ever, and the insults fly thick and fast.

The way some people talk, you’d think society is on the brink of snapping in two, as if tomorrow we’ll all be out on the streets with pitchforks. But arguing about ideas is as old as humanity itself. History’s big shifts rarely happened because everyone politely nodded while letting the other side finish their sentence. No collisions, no progress.

So in this article, let’s take a step back: what exactly is polarisation, where does it come from, and is it really as terrifying as the headlines make out?

Polarisation is nothing new. Think of the Reformation, which sparked a century of war across Europe. The German Peasants’ War, the English Civil War, the French Revolution, the American Civil War, communist uprisings in the early twentieth century, battles with the fascists in Italy and Spain, the terror campaigns in Northern Ireland and the Basque Country — the list goes on. Anyone claiming that things are worse than ever is, frankly, short‑sighted.

Not that there’s nothing new under the sun. Some phenomena today are genuinely different. We’ll get to that. But it helps to keep things in perspective. Violent conflict has spectacularly declined over the centuries, a trend that still continues. Psychologist

breaks it down in this talk:Even if we zoom in on the past fifty years, the actual substance of political disagreements hasn’t really grown wider. What has changed is that people react more emotionally, and social media simply puts those emotions on display.

I’m writing this from Bulgaria, the second most polarised country in Europe after Turkey, and far more so than the United States. Yet people aren’t brawling in the streets. Unlike in America, where every casual chat seems to collapse into a rant about that dreadful Trump or those loathsome liberals, Bulgarians keep their lips sealed. Politics is something you don’t bring up if you value the peace. Last year I asked about an election poster. A local warned me: “Don’t start.” So much for polarisation; you barely notice it here.

So, after an exploration of the term, what’s in store if you read on?

The ugly side of polarisation. Bitter group clashes, stalled cooperation, and a few headaches for democracy.

Does it always lead to violence? Usually no… but history has its spicy exceptions.

Why the US is tearing itself apart, and why Europe, for now, plays by different rules.

What people really fight about. The timeless triggers that set tribes against each other.

The hidden perks of polarisation. Yes, sometimes a good row gets things moving.

About “fixing” it, and why that isn’t a very tolerant idea.

The left shouts loudest. It polarises, then wags its finger.

Or is it a revolt against the elite? When the well‑educated few meet the frustrated many.

Buckle up, we’re diving head‑first into the world of polarisation.

So, what exactly is polarisation?

Polarisation is what happens when opinions collide.

To really understand it, you need to separate two things. First: how far apart are people’s views? How much distance is there between the positions in society? That’s called ideological polarisation. Second: how emotionally do people experience those differences? How heated do the feelings get? That’s affective polarisation.

Both vary wildly from country to country. Sometimes people face off red‑faced and shouting, even though their actual disagreements are tiny. Other times, the ideological gulf is enormous, yet mutual respect survives. But in general, the two forms tend to move together: the further opinions drift apart, the more friction you can expect.

Usually, polarisation takes the form of group polarisation. Like‑minded people huddle together and start battling the “other side” as if it’s a single, monstrous blob. Stereotypes harden. Flaws inside the group are glossed over, while the out‑group is seen as hopeless. No one listens to them anymore, while everything your own team says is swallowed whole.

Group dynamics discourage individuals from floating controversial ideas or suggesting alternative solutions. Independent thinking, outside influences, and creativity? Brushed aside. Within the group, people develop an illusion of invincibility, a smug certainty that we are absolutely right.

And that’s where the trouble starts.

The downside of polarisation

The dangers of polarisation often get overhyped. But that doesn’t mean we can shrug them off. Because the downsides are very real.

1. Among the like‑minded, people drift to extremes

Put a group of like‑minded people in a room, and watch what happens: their views don’t just reinforce, they intensify. This is group polarisation in action. Moderate opinions fade away, and society splinters into ever‑sharper extremes.

Experiments have proved the point. Researchers divided random citizens into groups by ideology — some left‑leaning, some right‑leaning — and asked them to debate flashpoint topics like same‑sex marriage, affirmative action, and climate measures. Before and after the discussion, participants wrote down their personal views. After talking to fellow believers, the results were clear: the left went further left, the right shifted further right.

Inside the group, members share arguments that confirm what they already believe. Doubts fade; counter‑arguments are never heard. Dissenters keep quiet under peer pressure. Over time, group identity fuses with group opinion: there’s an “us” and a “them.” The out‑group is caricatured, painted with negative traits, while your own side looks nobler than ever.

2. Distrust, bias, and failing cooperation

Another experiment illustrates the problem from a different angle. Researchers built mock hiring panels to pick a new marketing manager. There were three candidates. Each member got partial, biased information about each candidate, nudging the individual to prefer a different candidate. In reality, one candidate was clearly best. But the committees almost never chose them.

Why? Each panelist championed “their” candidate and barely exchanged critical info. All the energy went into defending personal favourites. In the end, the best evidence never made it onto the table.

That’s polarisation in miniature: it strangles cooperation. People stop seeing opponents as potential partners and start seeing them as obstacles. Nuanced positions are dismissed as weak or treacherous. Outsider arguments aren’t even heard; fresh information is filtered out in the hunt for self‑confirmation.

Polarisation sustains falsehoods in echo chambers where no one dares challenge the narrative. Within tight groups, misinformation spreads easily. Insider claims are swallowed whole, outsider facts are distrusted. The result? A society splintered into sealed bubbles, with little contact or mutual understanding. Shared problems become harder to solve. Compromise fades. A collective vision of the future frays.

3. Democracy under pressure

As groups drift apart, moderates get drowned out. Compromises become politically toxic. Brokers in opinions and interests, generally known as politicians, can no longer sell concessions to their base. Democracy slows to a crawl: difficult issues get kicked down the road, or politicians strike messy deals that save face but solve little, adding layers of bureaucracy or inflating public debt in the process.

Over time, citizens disengage. Some give up because the national interest no longer seems to come first. Others walk away because they can’t stomach the hostile political climate.

4. Radicalisation and lone wolves

In highly polarised settings, extreme opinions can circulate unchallenged. But does polarisation breed radicalisation? The evidence says: not really. Radicalisation is a messy process, and polarisation doesn’t flip the switch. Still, it can create fertile ground, especially when groups feel excluded, wronged, or under threat. More on radicalisation will follow in another article.

The link is weak when it comes to organised extremist movements. But it’s stronger for lone wolves: isolated individuals, often troubled, who slide further into radical ideas and eventually erupt in violence. Some start as obsessive consumers of news or online forums. Terrorists Anders Breivik in Norway and Volkert van der Graaf in the Netherlands both marinated in ideological echo chambers, far‑right for Breivik, far‑left for Van der Graaf, though of course personal and social factors also loomed large.

Polarisation may not lead to terror. But it can quietly erode trust, cripple cooperation, and fray the social fabric, long before anyone lights a match.

Polarisation in the United States

Normally, I focus on Europe. The world hardly needs another think‑piece on American politics. But this time, there’s no avoiding it: to understand polarisation, we need to look at the United States, a political theatre that, from across the pond, can look almost hysterical.

The history of political polarisation in the United States

America’s modern party system traces back to 1828, when Andrew Jackson led a rebellion against the Washington elites. His new Democratic Party drew its strength from agrarian and regional interests, united in opposition to the centralising, big‑capital forces around the federal government and the national bank.

On the other side gathered Jackson’s opponents, eventually in 1854 as the Republican Party. For a long time, the ideological differences were modest. The “winner‑takes‑all” electoral system encouraged broad appeal. Parties were more like loose networks and recruiting machines than coherent ideological movements. Most battles were about regional interests.

For over a century, Democrats dominated the South. First, they resisted the abolition of slavery; later, they opposed civil rights for African Americans. Meanwhile, the party grew gradually more centralist and economically progressive, creating internal tensions that exploded under President Lyndon Johnson.

In 1964‑65, Johnson pushed through civil‑rights legislation that ended legal segregation. In doing so, he lost the loyalty of many white Southern voters. That was the turning point. The Democrats evolved into today’s progressive, multicultural party; the Republicans became the conservative party of the South. Only in the 1960s did the American two‑party system acquire the sharp ideological divide that now underpins a deeply fractured political and demographic landscape.

Today, virtually every aspect of American life: religion, race, geography, media diet, even personality traits, maps onto party preference. Elections feel less like policy debates and more like identity wars.

Social and economic shifts

Johnson’s policies triggered slow, uneven improvements for Black Americans. Meanwhile, the country transformed. Immigration reform in 1965 fuelled the growth of Latino and Asian populations. The U.S. urbanised, secularised, and got better educated. Rural America shrank; de‑industrialisation hit hard, leaving factories shuttered and communities struggling.

Federal power in Washington kept expanding, while the influence of individual states waned. Democrats increasingly relied on urban, higher educated, and minority voters, leaning into diversity policies and political correctness. In the process, they alienated many white working‑class and suburban voters.

The media and the rise of echo chambers

A key media moment came in 1987, when the Fairness Doctrine, which required broadcasters to present opposing political views, was scrapped. Almost overnight, commercial talk radio exploded, dominated by conservative firebrands like Rush Limbaugh.

The formula was effective: stir up outrage, keep audiences loyal, and sell ads. Listeners got news and commentary that only confirmed their worldview. Everyone found their own echo chamber.

Even today, talk‑radio listeners display stronger affective polarisation — that visceral “us versus them” hostility — than newspaper readers, TV viewers, or casual social‑media users. Older Americans, in particular, marinate in this media environment, while younger Americans, who tune out politics more often, are less polarised emotionally.

The shrinking centre

For most of U.S. history, success in a two‑party system meant courting the middle. Swing voters decided elections; moderation was a winning strategy. But the centre has eroded. Mobilising the base has become more important than persuasion of the moderate voter. Politics has turned more radical, which fuels more polarisation, which shrinks the middle further. It’s a self‑reinforcing cycle.

Breaking it would require both parties to want it broken. And they don’t. A loyal, fired‑up base is politically convenient. Donald Trump boasted in 2016 that he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” without losing support.

And it isn’t just about loyalty, it’s also lucrative. Polarisation is good for fundraising: the angrier your supporters, the more they donate. American polarisation now runs on identity, media, and money. It looks like a warning: once the centre crumbles, the feedback loop of division is hard to reverse.

Europe: a patchwork of polarisation

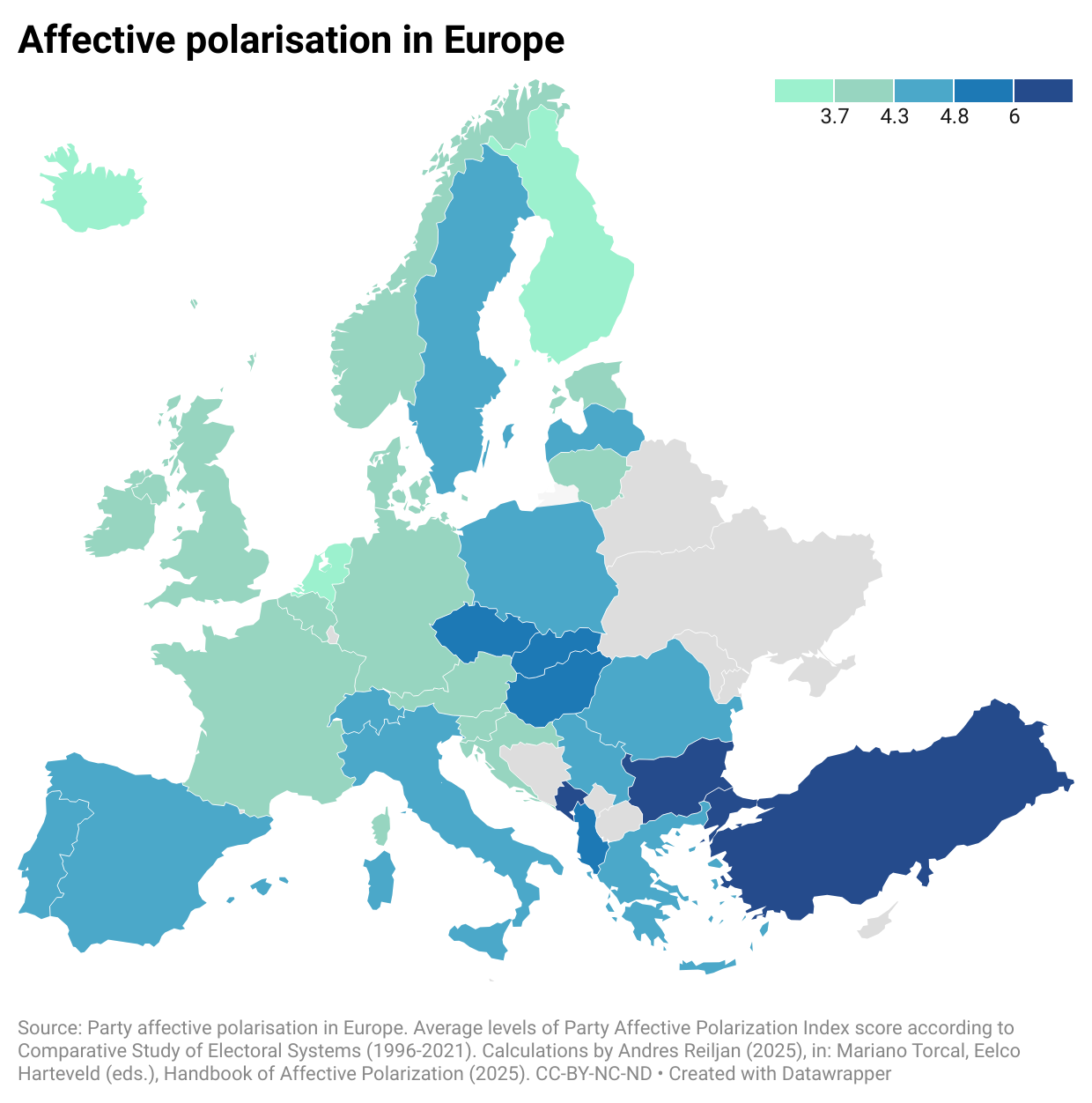

Compared with the United States, affective polarisation in Europe is harder to capture. This is a continent of patchwork histories: ethnic, cultural, and religious divides run deep, some tracing back centuries. Yet a few patterns emerge.

Broadly, Europe can be split into three zones:

Central and Eastern Europe. Here, affective polarisation has grown the fastest. Young democratic institutions collide with ethnic tensions and deep‑seated anti‑elite sentiments. Societies are more brittle; distrust of national government and urban elites fuels sharper “us versus them” emotions.

Southern Europe. Levels are middling. The main fuel is economic uncertainty, often amplified by inequality and the sense that power is hoarded in the capital. These societies are prone to swings of anger, but the emotional divide is less absolute than in the East.

Northern and Western Europe. The calmest zone. Politics here tends to rely more on consensus. Long democratic experience, relatively homogeneous populations, and institutional trust all keep affective polarisation lower.

Cross‑national surveys reveal striking differences:

Turkey tops the European charts, with an extraordinary score above 6. Bulgaria and Montenegro follow closely at 6.

At the other end, Iceland and Finland hover around 3.6, while the Netherlands sits below 3, the least emotionally polarised electorate in Europe. Dutch party supporters, on average, simply dislike each other the least.

For context, the United States scores 4.4, roughly the level of Spain and Poland. In other words: Europe contains polities far more divided than America, and some where political dislike is still remarkably mild.

The nationalistic right

Where affective polarisation rises in Europe, it is often tied to the rise of populist and nationalist right‑wing parties.

These parties thrive on sharp rhetoric and controversial positions.

Their presence alone raises the emotional temperature of debate, with references to fascism and nazism now routine in many public arguments.

Interestingly, the animosity is not symmetrical. Survey data shows that voters from mainstream, liberal or left-wing parties tend to strongly dislike nationalist right parties (think AfD in Germany, RN in France, Sweden Democrats, Vox in Spain, Flemish Interest in Belgium, PVV in the Netherlands). But the reverse is softer: many nationalist right voters hold less visceral hostility toward other parties than they receive in return.

Ancient fault lines

In 1967, sociologists Lipset and Rokkan published a seminal paper that mapped Europe’s political DNA. They identified four historical fault lines: deep social divides that shaped the continent’s politics and still echo today.

Centre and periphery

The first divide pits national state power against regional minorities, often with their own languages, cultures, or identities. This conflict emerged during state formation, when central authorities met local resistance. Classic examples include the north–south divide in Italy and the autonomous aspirations of Catalonia and the Basque Country in Spain. These tensions continue to fuel political and social polarisation. Consider also, for example, Latvia, where the party of the Russian-speaking minority arouses disgust among ethnic Latvians.Church and state

Europe has long wrestled with the question: Who defines public morality? Religious authority or secular power? In many countries, secularisation gradually eroded the influence of churches. In some post‑communist states, the divide is often generational: older citizens are more conservative and religious; younger cohorts are more secular and liberal. In Poland, the conservative and devout support Law and Justice (PiS), while the liberal, more secular electorate backs Civic Platform.Countryside and city

Another enduring divide runs between rural and urban life, or in economic terms, between agriculture and industry. Cities are typically more educated, cosmopolitan, and progressive, while the countryside tends to be less educated, traditional, and community‑oriented. In Switzerland, for example, conflicts between urban and rural cantons create more tensions than you might think.Capital and labour

The rise of industrial capitalism introduced a new axis: class conflict. It became the foundation for labour movements and demands for redistribution, shaping Europe’s left‑right politics for over a century. The differences between rich and poor, the right and the left, are a source of division in many countries, for example in Spain.

Polarisation in Europe is therefore more complex than simply a matter of left versus right. And to make matters even more complex, the fault lines often overlap. Poor rural areas, where the church has more influence, are pitted against wealthier, secular, progressive city dwellers. Hungary is a prime example.

The other divide: the people vs the elites

Lipset and Rokkan focused on structural divides, but there’s another line that has always been visible: elites versus the ordinary citizen.

Historically, this took the form of nepotistic family networks, where jobs, contracts, and political positions often flowed through clan‑like patronage systems. Outsiders to these networks felt shut out, fuelling resentment and polarisation. Especially in Southern Europe this tension is still very present.

In North‑Western Europe, the old family‑ and class‑based system has weakened. Societies became more meritocratic, and hereditary privilege lost some of its grip. But a new hierarchy emerged in its place: education.

In the Netherlands, surveys show education level is now the strongest predictor of political difference. Across much of Western Europe, higher education maps onto liberal, urban, and pro‑EU attitudes, while lower education levels correlate with more conservative, nationalist, or eurosceptic views. Europe is increasingly becoming a meritocracy of schooling, where cultural and political divides run along the diploma line.

In praise of polarisation

Back in 1950, the American Political Science Association released a report on the state of U.S. democracy. Its verdict was surprising: the country’s two major parties, Republicans and Democrats, were too similar. Their platforms overlapped so much that voters struggled to see meaningful differences. The political climate felt tepid. The authors offered an unusual prescription: more polarisation.

That irony still resonates. Low polarisation leaves citizens unmotivated, disinterested, and absent from the polling stations. High polarisation ignites passions but makes compromise painfully difficult. Which is better? Could there be an optimal balance, where political engagement thrives without tipping into dysfunction? And if we fall short of that balance, is intervention required?

The case for staying home

Polarisation moves people, but is that really what we're after?

Public policy is complicated. Most citizens cannot, and arguably cannot be expected to, trace the cascading consequences of tax plans, energy policies, or healthcare reforms. Simplification, or emotional storytelling, is often the only way to mobilise attention. Campaigns reach for gut‑level appeals, turning politics into a sort of showbusiness for ugly people.

From that perspective, is it so terrible if uninformed voters stay home? A quiet form of political abstinence may even show self‑awareness: if the choices feel opaque and the stakes abstract, staying out of the fray can be rational.

The beauty of conflict

And yet, there is something beautiful about polarisation rooted in principle. Citizens who are willing to pay the social cost of conflict, to argue with friends and family, to risk exclusion from their communities, do so not for personal gain, but because they believe their country’s future is at stake.

We should not sneer at such engagement. Politics is, after all, the arena where ideals and interests collide. As in private life, real conflicts are often loud and messy. Families fall out over inheritance, faith, or morality; neighbours quarrel over fences and property lines. Why expect national politics to remain serene, when the stakes are far greater and millions are involved?

Polarisation as a driver of progress

History is full of transformations born of polarisation. Movements for religious freedom, the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, and marriage equality all began in conflict. Activists were once dismissed as extremists or cranks. Without their provocation, social change would have come far more slowly, or not at all.

Polarisation broadens the pool of arguments. When consensus dominates, unconventional ideas are smothered. In a fragmented landscape, each group contributes its own reasoning, sharpening its arguments and challenging the majority narrative. Small or radical groups can finally be heard instead of vanishing into a grey fog of enforced civility.

This dynamic can unite the unheard. Scattered individuals who suffer in silence can coalesce into a movement, creating the visibility and momentum needed for reform. The environmental and gay rights movements of the 1970s are classic examples.

Fanatics sometimes know better

Polarisation is not always born of ignorance; it can also come from hyper‑awareness. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the European Commission signed enormous vaccine contracts, including a €35‑billion deal with Pfizer in May 2021. It bypassed the usual tendering process and was brokered via private text messages between Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Pfizer’s CEO — messages never released to the public.

At first, those who raised alarms were branded as conspiracy theorists — the “Covid cranks” muttering about shadows and smoke. Yet their dogged activism forced closer scrutiny. Today, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office is conducting a formal criminal investigation into possible corruption and conflicts of interest.

Sometimes, moderation doesn’t reflect wisdom. It can also indicate laziness, apathy and uninformedness.

Polarisation is double‑edged: it can corrode trust and paralyse compromise, yet it can also awaken societies, force uncomfortable debates, and give the voiceless a platform. In democracy, friction is not necessarily a flaw. It is often the engine of progress.

Should we intervene?

, the American legal scholar and former senior adviser to President Barack Obama, has spent years studying polarisation. He has written multiple books warning about its dangers, and, crucially, advocating intervention.Sunstein’s approach resonates with the thinking behind the European Digital Services Act. In his view, social media and news platforms should not leave users cocooned in their own echo chambers. They should be nudged or even compelled to encounter dissenting voices and unexpected perspectives. Public broadcasters, he argues, should act as bridges between groups that rarely speak to one another, sustaining a shared national conversation. And Sunstein does not rule out censorship of extreme opinions online.

Even in its moderate form, his vision involves coercion. It limits the freedom of both platforms and individuals to post, read, and curate content entirely on their own terms. All in the name of reducing polarisation. But to what end? Strengthening democracy? Against what threat, exactly? Such measures presume that democracy is in genuine danger, a claim that is not easy to substantiate.

At its core, democracy is brutally simple: the majority decides. The quality of deliberation, the number of arguments exchanged, the mutual respect between winners and losers: these are luxuries, not essentials. Polarisation certainly makes compromise harder, and media exacerbate the tension, but democracies do not cease to function because voters despise one another. They function as long as votes are cast and counted.

Sunstein’s interventions, then, raise a paternalistic question. Is he seeking optimisation, pacification, civilisation? Or simply elite stability? His programme can sound like a doctor proposing to amputate a leg to solve the patient’s limp.

Polarisation: a left‑wing obsession?

An American survey in 2022 revealed a striking pattern: Democrats worry about polarisation, while Republicans fret about immigration and the rising cost of living. Anecdotally, this rings true, but has never been properly researched. The progressive instinct is to seek connection, inclusion, and solidarity, and to frame polarisation as something inflicted by the right.

Yet this concern is not just unbalanced; it is ironically self‑incriminating. Multiple studies suggest that affective polarisation, the tendency to dislike and distrust political opponents, is actually stronger on the left. Supporters of green and progressive parties are generally more hostile toward the other side.

A recent German study, spanning ten European countries, confirms it. “Left‑wing voters often have warm feelings toward their own group, but they feel stronger resistance toward the opposing group,” explains Baldwin Van Gorp, a Flemish scholar of media. Conservatives, by contrast, tend to dislike their opponents less intensely, even if they disagree with them profoundly.

The paradox is clear: those most troubled by polarisation may also be the ones feeding it most viscerally.

Polarisation as revolt against the elite

There is a dimension of polarisation that rarely makes the headlines: its role as a backlash against elite formation, and in particular, against the rise of the educational meritocracy. This tension is likely to shape European politics for years to come.

The chattering class

Who really sets the tone in Northern and Western Europe? The Dutch geographer

coined an evocative term: the chattering class. These are people with academic credentials and strong social skills, but little applied expertise.They are not the engineers, doctors, or mechanics, people who actually make or repair things. Nor are they the bookkeepers, entrepreneurs, or forklift drivers. The chattering class earns its living by talking and writing: consulting, advising, drafting reports, opining on public platforms.

This class defines the problems, dictates the language, sets the moral tone, and frames the range of respectable opinion. Its influence does not come from sheer numbers, but from privileged access to media and policy networks. Its worldview is presented as universal and rational, but often reflects its own social position and cultural taste.

Politically, this class tends to lean left, in contrast to the more pragmatic or conservative working and middle classes. Reliable statistics are scarce; these professions prefer to maintain an air of neutrality. But the pattern is consistent:1

The third to seventh powers

The first and second powers, parliament and government, are ultimately accountable to voters. But the third through sixth powers are not: civil servants, judges, journalists, teachers. And their ideology doesn’t align with that of the population. In many European countries, their ideological centre of gravity tilts leftward, well beyond the balance of the electorate. (For scientists, the seventh power, there is little data available, but American research indicates similar results.)

The causes are obvious and have nothing to do with competence.

Most really want to carry out their duties unbiased, but even without explicit activism, bias seeps in. Journalists and teachers may unconsciously emphasise themes like climate change, inequality, diversity, and racism. Language itself carries ideology: talking about “rights” to social benefits, or framing left‑wing positions as rational and empathetic, while presenting right‑wing positions as cynical or extreme.

Judges interpret open norms, “reasonableness”, “public interest”, “due care”, through the lens of their own milieu. Collegial pressure reinforces the pattern: overtly right‑wing judges learn to keep their views private if they wish to avoid career isolation.

Civil servants can, often unconsciously, nudge policy through framing options, drafting advice, and emphasising certain priorities: sustainability, inclusion, social justice. Recruitment and professional networks, too, tend to self‑select for like‑mindedness.

In short: the state and its adjacent institutions are not as politically neutral as they should be.

Polarisation? Or revolt?

It is telling that complaints about polarisation mostly come from the centre and the left. Their tone is often indignant, condescending, or gently admonishing. By contrast, the right rarely laments polarisation. The reason may lie in the power asymmetry. What the establishment calls polarisation, large segments of the population experience as resistance. Resistance to a soft but pervasive dominance of the chattering class. To them, this is not mindless division but an uprising:

against a cultural narrative that claims neutrality while masking its class origins,

against institutions that speak in one moral register,

and against a hidden ideological monopoly that touches media, bureaucracy, the judiciary, and education.

Polarisation, in this light, is democracy in action: a revolt against a quiet hegemony.

The hidden power of top bureaucrats

Among all the forces shaping modern governance, senior civil servants may be the most quietly powerful. Anyone familiar with the machinery of the state knows that bureaucrats often wield more enduring influence than the politicians nominally in charge.

Ministers are, in the eyes of many officials, amateurs and transients: opportunists and media performers, swept into office on a tide of political mood. Politicians can, of course, exert bursts of real authority, but usually within the script written by their departments, or otherwise too erratic to plan around. Behind closed doors, the minister is seen as part fixer, part spokesperson, part oversized toddler to be managed. The department’s role is to keep the show running, and the minister entertained.

Civil servants, by contrast, prefer the shadows. They are most effective when invisible, and any limelight risks provoking ministerial jealousy. As a result, the inner life of the bureaucracy remains obscure. That is why a recent Danish study of the entire top echelon, conducted anonymously, is so revealing, and helps explain Europe’s polarisation puzzle.

How the bureaucracy sees itself

Senior officials imagine themselves as engineers of a vast and delicate machine. The state must adapt constantly to outside pressures: political swings, economic crises, migration waves, technological disruption, climate change, and geopolitical shocks.

They see stability as the prime directive, followed closely by managed progress, economic and social alike. And their ideological compass points left-of-centre. They are instinctively progressive, redistributive, technocratic, and cosmopolitan:

They believe in welfare states and social justice.

They see inequality, climate risk, and sustainability as unavoidable policy priorities.

They are convinced that long-term rational management trumps the passions of the street.

Public opinion, in this worldview, is a problem to be managed, not a partner to be trusted. Ordinary citizens are prone to fear, prejudice, and resistance to change. Hostility to the EU, globalisation, or technology is dismissed as irrational panic. If the public doesn’t agree, the assumption runs, it is because “we haven’t explained it well enough yet.”

In short: there is a cultural chasm between a technocratic, progressive elite and a more anxious, ignorant electorate.

The unstoppable bureaucracy

In theory, civil servants are servants of democracy: loyal executors of the government’s will. In practice, they often see voters, politicians, and media as irritants to be managed. Decades of public‑administration research point to systemic forces that make bureaucracies hard to control.

Even when a government comes in with a clear right‑wing or populist mandate, if its agenda conflicts with the progressive-technocratic worldview of the civil service, the full repertoire of obstruction comes out:

Endless procedural and legal complications.

Strategic delays and “further studies”.

Soft resistance through internal networks or links with the media.

This is not a paranoid fantasy. It has surfaced in public controversies across Europe. Administrative obstruction is rarely studied. Public administration studies are lacking in this area. But some right-wing politicians do complain about it.

In the UK, former prime minister

accused a tiny core of activist officials of undermining her reforms. Claims echoed by Dominic Raab and Suella Braverman, who spoke of a “clump” of left‑leaning lawyers and civil servants blocking key policies.In the Netherlands, the PVV left the government in 2025, citing slow‑rolled migration policies. Independent research confirmed significant bureaucratic obstruction. Writer

, no ally of the PVV, even reported that officials had privately promised to “throw sand in the gears” if the party ever governed.Critics will argue that incompetent ministers always blame the machine. That is partly true. But it may also be true in both directions: some ministers fail to master the machinery, while parts of the machinery quietly resist the voters’ will.

And that, in essence, is how a meritocracy slides into a soft oligarchy, one where policy flows downward from an unelected, self‑perpetuating administrative class, and polarisation becomes the people’s only tool of resistance.

Rethinking polarisation

Polarisation is often cast as a looming threat to society. And it certainly carries risks. It can fuel groupthink, erode trust, cripple cooperation, and strain the machinery of democracy. In its most extreme form, it can even prepare the ground for radicalisation.

Yet the story is not so simple. Polarisation is as old as politics itself, and history suggests that conflict can be creative. The great leaps of social change, religious freedom, women’s emancipation, civil rights, were born of clashing convictions, not quiet consensus. To care enough to disagree is, in its own way, a form of civic engagement.

Today’s polarisation is most loudly decried by the centre and the left, yet it also functions as a pushback against the dominance of a highly educated, metropolitan elite in media, politics, and the civil service. What appears to some as a dangerous fracture feels to others like a necessary counterweight to a worldview presented as self‑evident.

Attempts to engineer consensus, for example, by regulating social media or policing speech, carry their own dangers. They risk paternalism, even a soft form of anti‑democracy, by placing control of the public square in the very hands that are already objects of public suspicion.

At its core, democracy is disarmingly simple: the loud, the angry, and the unpolished count too. To see polarisation solely as a pathology is to miss its double edge. It is a mirror of society. Sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes hazardous, yet also an engine of renewal.

For further reading

Seymour Martin Lipset, Stein Rokkan, Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments, in: Seymour Martin Lipset, Stein Rokkan (ed.), Party systems and voter alignments: cross-national perspectives (1967)

, The better angels of our nature. Why violence has declined (2011)

Pim Fortuyn, De puinhopen van acht jaar paars (2012)

, #Republic. Divided democracy in the age of social media (2017)

Mark Bovens, Anchrit Wille, Diploma democracy. The rise of political meritocracy (2017)

Murat Somer, Jennifer McCoy, Déjà vu? Polarization and endangered democracies in the 21st century, American Behavioral Scientist (2018)

Andres Reiljan, Fear and loathing across party lines (also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems, European Journal of Political Research (2019)

, Why we’re polarized (2020)

, Polarization, democracy, and political violence in the United States: what the research says, Carnegie Endowment For International Peace (2023)

Quita Muis, “Who are those people?”, Causes and consequences of polarization in the schooled society (diss., 2024)

Levi Boxell et al., Cross-country trends in affective polarization, Review of Economics and Statistics (2024)

, Ten years to save the West (2024)

, Driftet unsere Gesellschaft auseinander?, lecture Forum Wissenschaft, Wirtschaft und Politik (2024)

Anders Esmark et al., How technocratic is the power elite? A new approach and evidence from a mixed-method study of the Danish power elite, New Political Economy (2025)

Mariano Torcal, Eelco Harteveld (ed.), Handbook of affective polarization (2025)

Laura Smith, Emma Thomas, A primer on politicization, polarization, radicalization, and activation and their implications for democracy in times of rapid technological change, British Journal of Social Psychology (2025)

This was the sixth episode in the series on censorship and free speech.

Bansko, 2 August, 2025

Left-right division based on the RILE score of political parties by the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP). Electorate distribution based on the average of the results of the three consecutive House of Representatives elections from 2017 to 2023. Political preferences of civil servants are taken from a 2021 poll among the Civil Servants Panel, with 1,446 participants. Political preferences of journalists are taken from M.J.P. Deuze, Journalists in the Netherlands (diss., 2002). Political preferences of teachers are taken from a 2019 survey by Regioplan among 10,000 AOB members. The picture is likely somewhat distorted by the union membership of the respondents, but better figures are not available. The political preference of judges is derived from a combination of two surveys: a 2008 survey by Vrij Nederland among judges, and a 2010 survey among prospective judges and public prosecutors (RAIOs).

Fascinating article. Thanks for this!

A reader from North Macedonia added that he's under the impression that in many former socialist and communist Eastern European countries the polarisation from the right is heavier than from the left. Where in Western Europe it's often the nazism/fascism trope coming from the left, in Eastern Europe it often concerns fearmongering for the regressive socialist or communist leanings of the left.

Meanwhile, he's also under the impression that the 'chattering classes' in his region are equally left-leaning.