Political toleration

On this page, you will find an overview of the articles about political toleration.

Toleration is about allowing something controversial. In the case of politics, the element of controversy concerns both political views and behaviour together. Citizens have a political opinion, they propagate it, and they want to realise it (together with others) by doing something. Political toleration exists when dissenting political opinions and actions are free.

This series on political tolerance includes:

The paradox of toleration. Should there be room in politics for opponents of democracy?

The party ban: proposals to ban political parties in a democracy.

How democracies can also become intolerant.

Ways to make democracies more tolerant.

The overview of the articles in this series is below.

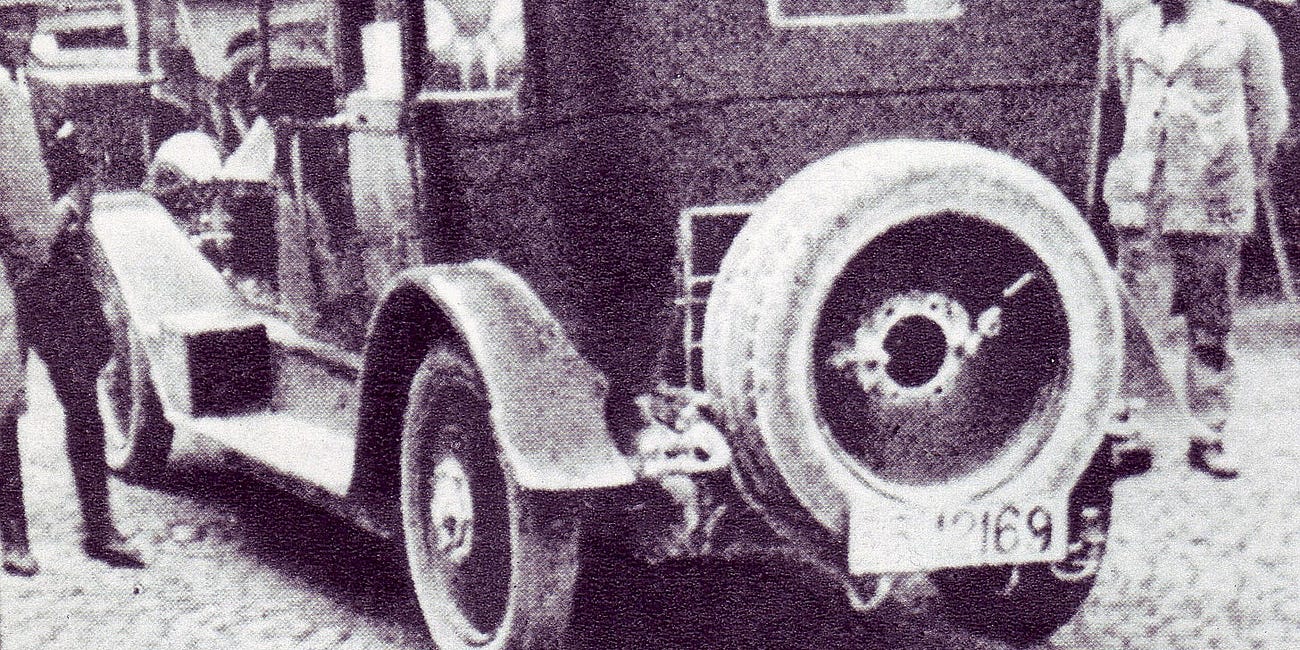

How Mussolini had a leader of the opposition assassinated

On June 10, 1924, Giacomo Matteotti, aged 39, left his home in northern Rome on foot on his way to the parliament library. He came there often: as a prominent member of parliament, he was known as a studious and thorough person. But he was also often stubborn and angry: among his fellow party members he was nicknamed Tempesta, thunderstorm. His family c…

What if the voter is fed up with democracy?

This series on political toleration focuses on a classical problem, the so-called paradox of toleration. Democracy is a form of political toleration: any party can participate, even parties that many people strongly dislike. The question is: how much room should opponents of toleration be given in a tolerant system. Characteristic of tolerant systems is…

Should there be political toleration for intolerance?

In the previous newsletters, we successively discussed the fascist terror of Mussolini and historical situations in which the voter was fed up with democracy. We came to remarkable conclusions: The result has almost always come about under heavy pressure, violence and manipulation.

For these reasons, banning anti-democratic parties is a bad idea

This is the fourth newsletter in the series on political toleration. Earlier, we dealt with the emergence of Fascism in Italy in 1924, historical situations in which the voter had had enough of democracy, and philosophical reflections on the paradox of toleration

These are good arguments for banning a political party

We have already discussed poor arguments for banning parties in another newsletter. Well, actually I should formulate that more benevolently: less strong arguments. And in the previous newsletter, we looked at really good arguments for not creating the opportunity to ban anti-democratic parties.

When should a political party get banned?

Earlier newsletters discussed arguments for and against the possibility of banning anti-democratic parties. Central to it was the paradox of toleration: whether opponents of toleration should be tolerated. In this newsletter we briefly summarise the arguments against a party ban. After that, we will expand on the concept of

How democracies can become tyrannical

The previous newsletters in this series were about how to deal with anti-democratic movements. But the majority of the people rarely knowingly elect a tyrant. I wrote that before. A much bigger problem are the coup d'état and democratic leaders gradually turning into tyrants. We’re not talking about coups here. This newsletter is about

Better alternatives for parliamentary democracy

In this last newsletter in the series on political toleration we will conclude this topic. Political toleration is about attitudes and behaviour together. Citizens have political opinions, they propagate them, and they want to realise them (together with others) by doing something. Political toleration exists when dissenting political opinions and actio…